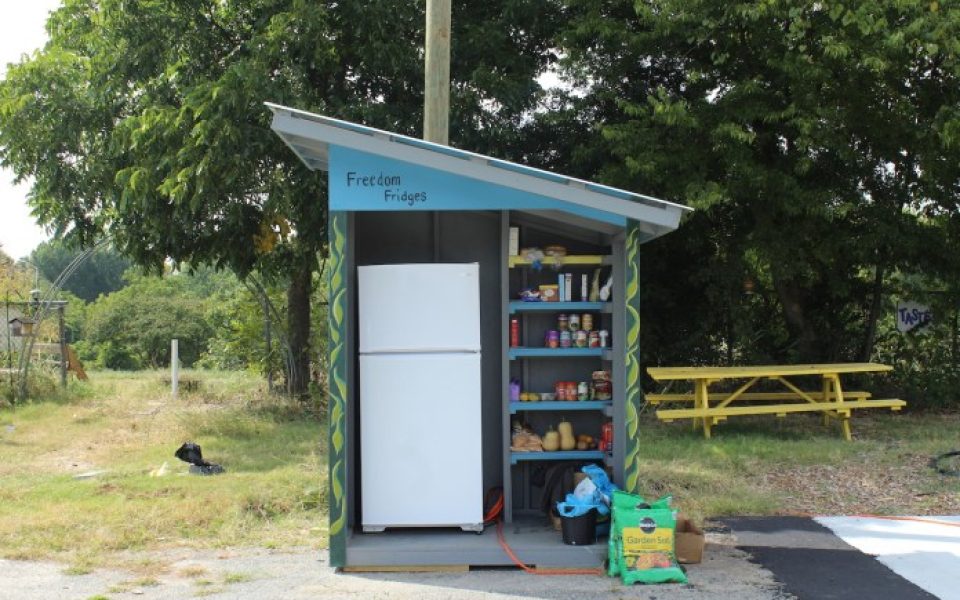

Featured photo: The city’s first Freedom Fridge is located in the parking lot of Prince of Peace Lutheran Church in the Warnersville neighborhood. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

Dozens of freshly-picked, bright-red chili peppers take up residence in the highest shelf of the fridge door, above a couple jugs of milk and packs of applesauce. In the belly of the fridge, deli meats, bags of grapes and cartons of eggs wait patiently for their turn to be picked. In the freezer, two unopened boxes of ice cream sandwiches beckon.

On a recent Monday afternoon, these are the items from which community members can choose from the first Freedom Fridge in Greensboro. Located next to the Prince of Peace Lutheran Church in the Warnersville neighborhood off of Curtis Street, the fridge aims to be a new kind of mutual aid in the city, one where fresh food is available for all.

“We started because of the pandemic,” says Alyzza May, an organizer with Greensboro Mutual Aid and co-creator of the Freedom Fridge. “We were seeing three basic areas of need in the city: housing, food and emergency cash assistance.”

The organization, which has been around for a little over a year, has been providing community members with goods and direct financial assistance in the form of Venmo or Paypal for months, utilizing platforms like Instagram and Facebook to offer help. Food had also been one of the most asked-for items, so the group began discussing the idea of creating a community fridge network, where people could donate and get food for free. Then, a couple of months ago, members of Greensboro Mutual Aid connected with two NC A&T State University students, Bray-Lynn Singleton and Ashley Mathew, to bring the idea of a community fridge to life.

“Because food was one of the things that we were getting inquiries around, this was a natural segue to do that,” May says.

On Aug. 29, the first Freedom Fridge in Greensboro was unveiled.

Currently, it sits next to the parking lot of the church in a shed painted by Terri Jones, a member of Greensboro Mutual Aid who grew up in Warnersville. A long, orange extension cord runs from the fridge into the church nearby.

The idea came from other cities who have created similar networks, May says.

“We saw it in other places,” they said. “The blueprints we had for the building originally came from a program in Chicago. There’s also fridges in Atlanta, and the first one I saw was in Brookline or Boston. It’s nice to see all of these networks. There are people all over the world doing this.”

That’s how Singleton, a senior at A&T, got the idea too.

“I found some community fridges on Instagram like in Houston and Miami and I wanted to find a way to do it in Greensboro,” she said. “I really wanted it to work in Greensboro because I felt like it would be good mutual aid for the city…. There’s a lot of food insecurity here, especially in east Greensboro.”

According to 2014 data by the Committee on Food Desert Zones, a legislative research commission created by the North Carolina General Assembly, there are 17 identified food deserts in Greensboro alone. There are 24 in Guilford County. A food desert is defined by the US Department of Agriculture as a residential area with a high level of poverty, where at least one-third of the residents live more than a mile from a grocery story. According to a map from 2014, most of the food deserts in Guilford County are located in the center of the county in south and southeastern Greensboro and also to the northwestern part of the county towards McLeansville. Much of High Point also is also considered to be an area of scarcity. And while these problems have existed for years, May said that the pandemic, like with virtually all aspects of society, has made food insecurity much worse.

“I think it has highlighted the problem immensely,” May said.

A huge part of alleviating problems during the pandemic has been the concept of mutual aid — giving and receiving without expecting anything in return.

“It seems like charity but it’s very much not,” May explains. “It challenges the charity model in general, which I think is very important because anyone can be someone who gives or who receives. We’re all teachers and we’re all learners. You’re not going to get a tax write-off for this. There’s no ‘good job’ for doing this. It’s the idea that we all have things that we can offer.”

That’s why May views the Freedom Fridge, which is run solely by volunteers, as fundamentally different from a food bank or another kind of charity. Namely, there isn’t anyone manning the fridge constantly. That means that giving and taking food is based on a shared understanding of need and trust.

“A big part of mutual aid is trusting that people are asking for what they need,” May explains.

And although they don’t really have a way to track how many people are using the fridge, they say that the items are turning over pretty quickly.

“A lot of people are engaging with it,” May says. “Community ownership is growing and that’s really important because we want there to be an implicit understanding that there is a need and that as a city, we have everything we need, whether it’s the people growing it or the people hoarding it. It’s a process of understanding what it is that we have to offer our neighbors. It’s a way to create community connection and empathy.”

Ben Tyson with the Sunrise Movement in Greensboro is a contributor to the fridge. As a hub coordinator for the organization, Tyson has been helping to grow produce at a community garden plot and has been taking vegetables like peppers to the fridge. So far, they’ve made about two or three runs he says. But in order to contribute more, he says that they’re working to partner with larger farms like the Urban Teaching Farm to increase production. It’s kind of like how he thinks about a bell pepper.

“A bell pepper is cheap and is full of seeds which become a lot more bell peppers,” he says. “You could sell a bell pepper, but it’s free to turn it into a bunch more peppers to meet other people’s needs. It’s the idea that we can collaborate with other groups and meet more people’s material needs.”

And collaboration and expansion will be key to maintaining the success of the Freedom Fridges, Singleton says. Eventually, she wants other entities like downtown businesses, grocery stores and more gardens to contribute to the fridge. That way, they can start placing more fridges around the city.

“We really want to inspire people in the community to get involved to get it widespread through Greensboro,” she says. “It’s something that anybody can get into. It’s a good way for people to get into activism or social justice. We need all hands on deck.”

The Freedom Frige is located in the parking lot at 1100 Curtis St. in Greensboro. To learn more about the fridge or to contribute, email [email protected] or follow @gso_mutual_aid and @gsocommunityfridge on Instagram.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply