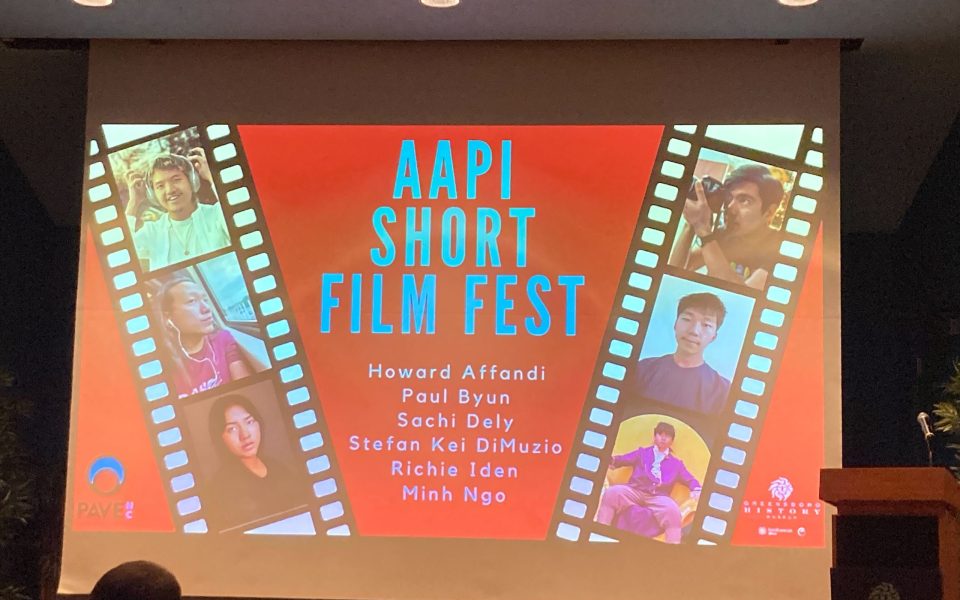

Featured photo: The city’s first AAPI Film Festival was held at the Greensboro History Museum on April 27. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

The length of a mother’s fingers, wanting to belong, shots of families eating, the humor in certain sounds.

At the inaugural AAPI Film Festival held at the Greensboro History Museum, the messaging across the screen was our shared humanity.

“I wanted to show that Asians are more than doctors or scientists,” said organizer and PAVE NC co-founder Tina Firesheets at the screening of the short films on April 27 ahead of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in May.

Firesheets, a local creative and writer, was inspired to organize a citywide AAPI film festival last year. But juggling a full-time job, her family and writing a book left her overwhelmed. So instead, she scaled down the idea, which resulted in a two-hour event where six local Asian filmmakers gathered to talk about their different films. And, according to Firesheets, a film event focused on the AAPI community in Greensboro, was a first.

“I am excited about the Greensboro/Triad community seeing films made by local AAPIs,” she said. “These films aren’t necessarily AAPI-themed, but this also proves that they don’t have to be.”

Among the creatives were Stefan Kei-DiMuzio, Howard Affandi, Paul Byun, Sachi Dely, Richie Iden and Minh Ngo. While they all represent parts of the AAPI community, they ranged in age and experience in filmmaking.

Byun for example, is a well-known commercial filmmaker in Greensboro who often makes work that highlights local businesses. His short films, “Kenya” and “World Chefs of North Carolina,” draw from Byun’s taste for humanizing differences between cultures for a general audience.

A world traveler, Byun — whose family came to the US from South Korea when he was 13 years old — jet sets every chance he gets to further his goal of broadening people’s understanding of different cultures through filmmaking. In his shorts, children play and men fish in different cities throughout Kenya while chefs from varying countries — France, Laos, Dominican Republic — show off their food for the camera.

At the end of his first short, Byun speaks during the ending credits: “After all, we’re not all that different, are we?”

His question acts as a throughline throughout the rest of the films.

In Sachi Dely’s film, “My Mother’s Hands,” Dely plays a fictionalized version of her mother, who has cared for her throughout her lifetime, from when her family had to flee Vietnam to when they immigrated to the United States to when she would tend to Dely when she was sick. While the story is a distinctly personal one that mirror’s Dely’s own history, the message is one of shared humanity: the love mothers have for their children and the lengths to which they’ll go to protect their kids.

After the screening, Dely admitted that her mother has yet to see the film.

“I’ll probably do a private screening for her,” she said.

The other films in the screening like DiMuzio’s “Vocafoli” and “Olivier” by Ngo featuring Affandi and Iden, had almost nothing to do with the Asian-American experience. Instead, they cast their characters in situations that almost any person viewing them would empathize with. In “Vocafoli,” viewers follow a man who wakes up one day and starts hearing all sound effects as human-made beatboxed effects, which understandably results in hilarity. In “Olivier,” the audience watches Ngo grapple with his pursuit of becoming an actor as he thinks critically about his race and the part it plays in his roles. (Oftentimes, he doesn’t think about it at all, he says in the film.)

And with that sentiment, Ngo explains one of the central inner conflicts that Asian Americans and other people of color in this country have to contend with.

How interesting are our stories because we are Asian American?

It’s a tricky question to contend with given that the title and draw of the event is that it’s an AAPI Film Festival. But once inside, viewers were left with the understanding that although we are Asian American, it’s not all we are.

“I love the diversity of the films,” Firesheets said during the panel discussion after the screening. “They’re not all Asian-themed. It shows that we can tell stories…. and that we are informed by these things but we are not bound by these things.”

In the future, Firesheets envisions growing the festival, possibly with sponsors and making it an annual event. It’s something she’s passionate about, even if she’s not the one planning it.

“I’m not a film expert or a filmmaker, I am just driven to raise the visibility of AAPIs in our community,” Firesheets said. “I welcome passing the baton.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply