A thin, red laser shoots from the user’s hand as they drag

and move jagged lines across a map of North Carolina.

The shifting boundaries outline a myriad of red and blue

hexagonal discs that span across the state; with each small alteration, two red

and blue bars in the lower left corner of the screen grow longer or shorter.

The name of the game? “Gerrymandering Madness,” and it’s free to play now at

the Greensboro History Museum.

The interactive attraction on the second floor of the

downtown museum opened as part of the institution’s new traveling exhibit from

the Smithsonian titled American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith. The installation,

which opened in December, runs until March 27 and aims to educate the public

about the history of democracy in the United States and its shifting definition

since the founding of the nation.

The gerrymandering simulator, which was created by Durham

company CrossComm, is played on an Oculus Rift and is installed in an area of

the museum titled “Connection Point,” a kind of game center that accompanies

the more straightforward walk-through exhibit.

Users put on a pair of virtual reality goggles and find themselves in a paneled room with a North Carolina flag in one corner and the American flag in the other. On the center wall is a screen which shows the map of North Carolina’s blue and red areas that indicate Republican and Democratic voters. Players use a remote control to shape the map to try and disenfranchise one party over another. On the desk in front of the screen is another state map that shows population densities for different areas which helps guide players on which lines to manipulate.

Here’s a look at Gerrymander Madness: The Anti-Democracy #VirtualReality game. We built this in partnership with @GsoHistryMuseum for their #ProjectDemocracy2020 initiative opening tomorrow! #gerrymandering pic.twitter.com/xm99IqRIOW

— CrossComm (@CrossComm) December 6, 2019

Glenn Perkins, the curator of community history at the

museum, explains how players can drag and drop lines around urban or rural

areas to change how votes weigh in elections.

“The idea is that it’s a game,” Perkins says. “It’s to try

and engage younger people. They’re gonna start to vote and think about how

things like this affect their vote.”

And even though the simulator is meant to just be a fun

addition, its presence speaks to the broader mission of the exhibit, which is

to educate viewers on the complicated ways that democracy has been both upheld

and degraded throughout the course of the country’s history.

“It just seemed like this year was such an important one in

terms of anniversaries,” Perkins explains, “like the 100th anniversary

of women’s right to vote and the 150th anniversary of 15th

Amendment which gave black men the right to vote, and the 60th anniversary

of Greensboro sit-ins, and it being a census year, on top of it being an election

year.”

The main exhibit can be viewed on the third floor of the museum

and starts with the founding of the United States. It chronicles how rowdy

colonists sought to separate from their British royal leaders and establish a

country for the common people. And yet, as viewers advance through the

installation, a recurring theme of disenfranchisement and the question of who

democracy serves comes up again and again. The exhibit outlines in exhaustive

detail, the number of groups of people who were excluded from voting throughout

the years starting with white men who didn’t own property, women, black freed

and enslaved people, all the way through to the passage of the 26th Amendment

in 1971, which lowered the voting age from 21 to 18.

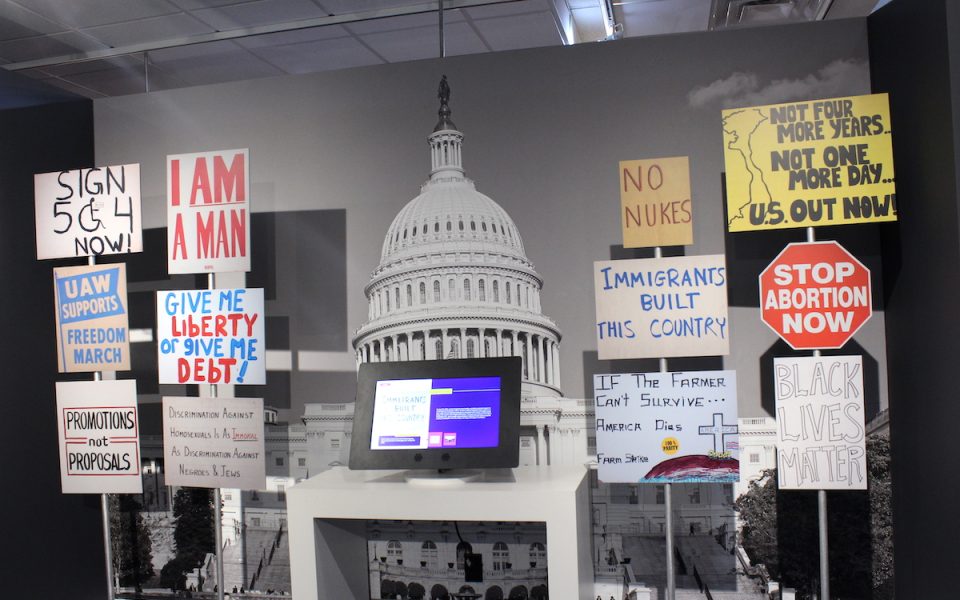

The exhibit also includes other manifestations of democracy such

as the right to petition and right to assemble.

-

Old political buttons on display at the exhibit (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka) -

Posters urgings people to register and vote (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

A display of posters from both national and local protests with

slogans like “Immigrants built this country” and “Stop abortion now” demonstrates

a wide range of political ideologies. Nearby, multiple screens play a rotating

playlist of past campaign ads by presidential hopefuls like Mitt Romney and

Donald Trump.

“One of the most important takeaways is the recognition that democracy has always been about conflicting opinions and dialogue and debate and disagreement,” Perkins says.

“It’s important to put some of our political disagreements of our current time in historical context to see that they are not entirely unique. They may be special for our age, but we’ve been arguing about these questions for nearly 250 years now.”

Perkins

also hopes the exhibit will remind visitors of the importance of voting and engaging

in the political process.

“We hope

the exhibit encourages people to see how they can play a role in our democracy,”

he says. “That when you put your voice out there, it can resonate over a long

period of time.”

American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith is on display at the Greensboro History Museum until March 27. Visit greensborohistory.org to learn more.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply