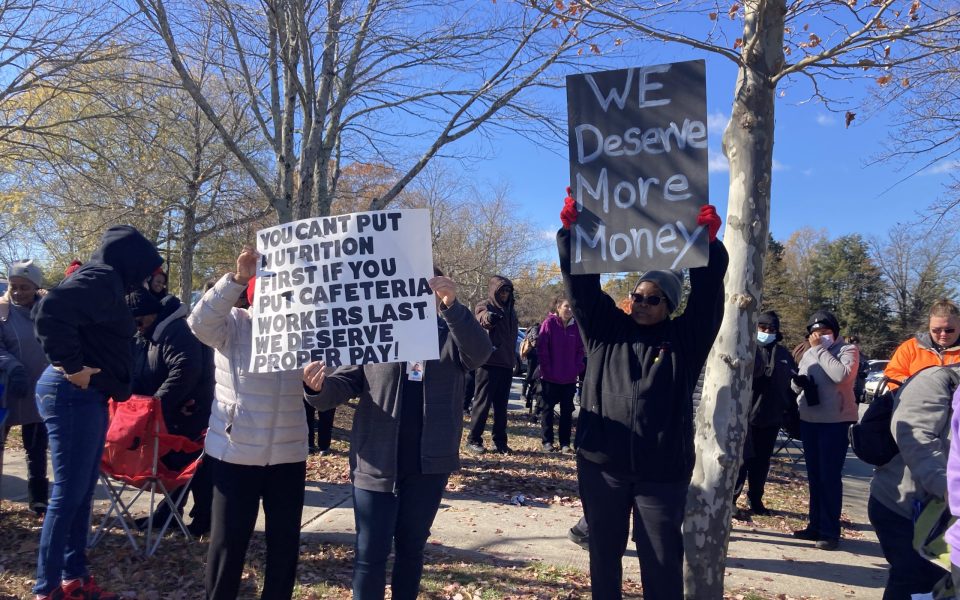

Featured photo: Guilford County Schools cafeteria workers hold up signs during a protest for higher pay on Nov. 27. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

There has been an update to this piece. Read more here.

“Thirty-five cents is not enough.”

“You can’t put nutrition first if you put cafeteria workers last.”

“Pay my mommy.”

“We deserve more.”

Those were just some of the statements displayed on signs held by Guilford County Schools’ cafeteria workers, who walked out en masse on Monday morning to strike for higher wages. By around 11 a.m., about 100 workers stood across the street from Guilford County Schools’ administrative office off of North Eugene Street in Greensboro. Many had been there for four hours, bundled up in heavy coats and scarves.

Kelly Shepherd, Eastern High School’s cafeteria manager, helped organize the effort to walk out on Monday morning. Shepherd said that he and others had been involved in negotiations with Travis Fisher, the district’s executive director of school nutrition services, for the past three weeks but that talks had broken down in the last few days.

The main thing workers are calling for is an increase in pay, Shepherd said.

Despite working for the district for 12 years, Shepherd said he is being paid about $18 per hour. And that’s only because the school district gave cafeteria workers a 2 percent raise after the state budget that passed last month excluded nutrition workers — who fall under the “classified staff” umbrella — from the standard 4 percent raise that other classified workers like custodians received. Bus drivers, who have also striked in the past for higher wages, received an additional average 2 percent salary increase on top of the 4 percent raise, according to reporting by Education NC.

Classified staff are required to make at least $15 per hour as of July 2022.

Kicking the can?

Because the pay increase did not include nutrition workers at the state level, the responsibility to pay workers has fallen to local jurisdictions.

In the spring, Guilford County Schools Superintendent Whitney Oakley announced that for the 2023-24 budget, they would ask for a $77.6 million investment from the county commissioners to address vacancies and increase pay for classified staff like nutrition workers. In the FY2024 adopted county budget, a line item shows that $15.4 million was approved by the county commissioners for Guilford County Schools “to support pay adjustments for classified employees.”

But workers like Kerri Fulk, who works with Shepherd at Eastern High School as an assistant manager in the cafeteria, said that nutrition workers haven’t seen any of that promised money.

She’s currently making $16.60 an hour after working within Guilford County Schools for 15 years.

Part of the problem, according to Shepherd, is that nutritional workers are part of a different pay structure compared to other classified employees. They also are paid a flat hourly rate rather than having a “STEP” pay structure, which pays employees based on years on the job.

For example, bus drivers, who are considered “Grade 62” employees, have a starting rate of $16.13 per hour, with an approximate 24-cent increase with every year of experience. That means if Fulk was a bus driver, she would earn $20.16 per hour after working for 15 years.

Nearby, Amy Wilder, a cook at Montlieu Academy of Technology in High Point, rolled up her sleeves to show the burns she’s sustained on the job. When asked how much she makes per hour, she responded by stating, “When you find out you let me know.”

She’s been with Guilford County Schools for seven years and said that she’s not sure how much she’s making right now. That’s because during the negotiation process today, Guilford County Schools agreed to another 2 percent raise for nutritional staff to get them to the same raise percentage as other classified staff, according to Shepherd. Guilford County Schools has not responded to TCB’s questions so we have not been able to independently confirm this fact.

Ahead of the walkout on Monday morning, Guilford County Schools put out at statement on their social media stating the following:

“We are aware some school nutrition staff are not working today. We are aware of the concerns raised by our school nutrition employees, and we are actively working to address these issues.

Our top priority is the well-being of our students, and we want to assure everyone that students will be served meals today. Thank you.”

Still, even with the total 4 percent raise, Wilder said it’s not enough. Currently, she believes with the additional 2 percent, that she would be making $15.60 per hour, just a 35-cent increase from before. Ahmad Haamad, a cafeteria manager who was trained by Wilder years ago, makes the same amount of money as Wilder because there’s no STEP pay.

“We work hard,” Wilder said. “We’re feeding your children, but we can’t even feed our own.”

Wilder and others who spoke to TCB cited increased cost of living in recent years, the effects of the pandemic and inflation as making it difficult to stay financially afloat.

Joanna Pendleton, president of the Guilford County Association of Educators, told TCB that according to workers at other school districts like Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools and the Charlotte-Mecklenburg district, that cafeteria managers are making anywhere from a dollar to $4 more than GCS employees.

“They’re figuring out a way to do better pay for their cafeteria folks, most likely through local funding,” she said.

When called to ask about additional funding for cafeteria workers, Guilford County Commission Chair Skip Alston declined to comment, stating that he was “walking into a meeting” at that exact moment.

Several employees also told TCB that they’d like to work full-time, which is at minimum a 6-hour workday, but they haven’t been able to secure full-time positions even as the schools hire additional cafeteria workers.

One such employee is Tonya Morgan, who has been working as a cafeteria substitute for the last two years. She’s making $15 per hour right now and because she’s part time, doesn’t receive benefits like healthcare. Others like Susie Spencer, who sat in a chair while bundled up in blankets, have to work two part-time positions to make full-time pay.

Spencer, who has worked for Guilford County Schools for 20 years, said that she makes about $15 per hour as an assistant server at Sedalia Elementary. She also works as part of the ACES afterschool program part-time to make money. That means that she’s at the school from about 9 in the morning until 6 in the evening. For the past few years, Spencer said she’s asked to work full-time hours in the cafeteria so she can get off earlier but that they won’t give her the extra two-and-a-half hours she needs to be considered full time.

“I want six hours in the cafeteria so I can go home at 1:30,” she said. “You know, after 16 years you get kind of tired, and our cafeteria needs the help.”

The issue of turnover and short-staffing is a problem at most schools, Wilder said.

“We’re doing the work of two or three different people,” she said.

The issue of worker shortage is not restricted to public schools, of course. During the pandemic, many companies struggled to hire employees and thus increased their hourly wages. Major companies like Starbucks, Target and Amazon increased their minimum wages to $15 per hour. When asked why they continue to work for Guilford County Schools despite having other options, Wilder said that she cares about the students.

“We do it for the children,” Wilder said.

She and Haamad also pointed to the flexible work schedules that allow employees to spend more time with their families during holidays and the summers when schools are closed. But ultimately, they love their jobs, Wilder said.

“You have to understand, we were doing this for $10, $12 an hour and nobody was saying nothing,” she said. “But at the end of the day, we still have to take care of our families.”

Fulk said her son, who is a teacher at Eastern Guilford High School, told her that the students are supporting the workers by ordering their own food for lunch today.

Pendleton also told TCB that they’ve seen broad support for the nutrition workers from across the county.

“I heard about one school where a lot of the students have decided to sit at the tables in the cafeteria and not eat to show solidarity with their cafeteria workers,” Pendleton said. “Everyone I’ve heard from today has been really, really supportive.”

According to Shepherd, the school district is currently working to figure out more funding for cafeteria workers due to the strike. He told TCB that the group is expecting a response from Superintendent Oakley around 4 p.m. this afternoon.

“It’s not just about today’s money, it’s about moving forward,” Shepherd said.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply