It’s a Sunday evening and Melvin McDuffie is mad.

He stands on a dirt road, a scowl scrunching up his face,

ignoring his brother Frank’s outstretched hand. He wears his Sunday best — a

crisp white shirt, dark khaki shorts and black shoes, the kind with buckles and

straps that criss-cross over the wearer’s feet.

McDuffie can’t remember exactly what he was mad about, but

he recalls the many Sundays like the one portrayed in Leo Rucker’s painting

like it was yesterday.

“That’s on Liberia Street,” says McDuffie, who is now in his

seventies. “I’ve got my Sunday shoes on and we’re standing on that dusty road.

We used to put petroleum on our shoes to get them to shine.”

The painting is a snapshot of a scene from McDuffie’s past,

one from his childhood decades ago when he was only about 3 or 4 years old. His

older brother Frank, who has since passed away, stands next to him while a

third character in the foreground captures the photo.

The work, titled “Shake On It,” is on display as part of

Winston-Salem artist Leo Rucker’s exhibition at the Southeast Center for Contemporary

Art. Rucker is a part of the museum’s Southern Idiom series which

highlights the diversity of artists in the city. Using historical photographs

from Old Salem, Rucker, who also works at Old Salem, produced nine paintings that

portray individuals and families that lived in Happy Hill, the historical black

neighborhood in Winston-Salem, during the 1930 and 1940s.

“Happy Hill was a thriving community for different generations,” says Rucker, who grew up in Winston-Salem on 14th Street. “The paintings represent the success of some of these families. I wanted to show, ‘What was life like across the creek?’”

After the abolition of slavery, many freed slaves bought an

acre of land on a hillside that eventually became known as Happy Hill. For

decades, the neighborhood was the epicenter of black life in the city. But

factors like racist housing practices, the construction of the city’s first

public housing units and eventually the construction of highway 52, which cut

right through the neighborhood, brought drastic changes to the once thriving

neighborhood.

In “Shake On It,” you can almost smell the savory scent of

post-church meals being served in the nearby homes, hear the unison cry of the

cicadas, feel the grime of the dirt and dust as it wafts in the air and settles

on your face, hair and every inch of exposed skin.

McDuffie dates the scene at about 1948. During those years,

he and his brother Frank would play near their neighbor Ms. Velma’s house while

their mom was visiting with her after church.

“It was a traditional Sunday,” he recalls. “You would go to

Sunday school and then go to the 11 o’clock service at church. Then in the

afternoon, at grandma’s house you’d eat. Fried chicken, okra, squash, corn,

beans. There was never a shortage. Then, you’d go see your friends and enjoy

the rest of the day.”

On other days of the week McDuffie remembers seeing

neighbors congregating on front porches, playing music while people danced in

the yards.

“Most of the folk

were hard-working,” he says. “Most of the folk loved and cared about each

other. That’s the kind of life you’d want. That’s the kind of neighborhood

you’d want. Why do you think you called the hill happy? Happy Hill was a

wonderful place.”

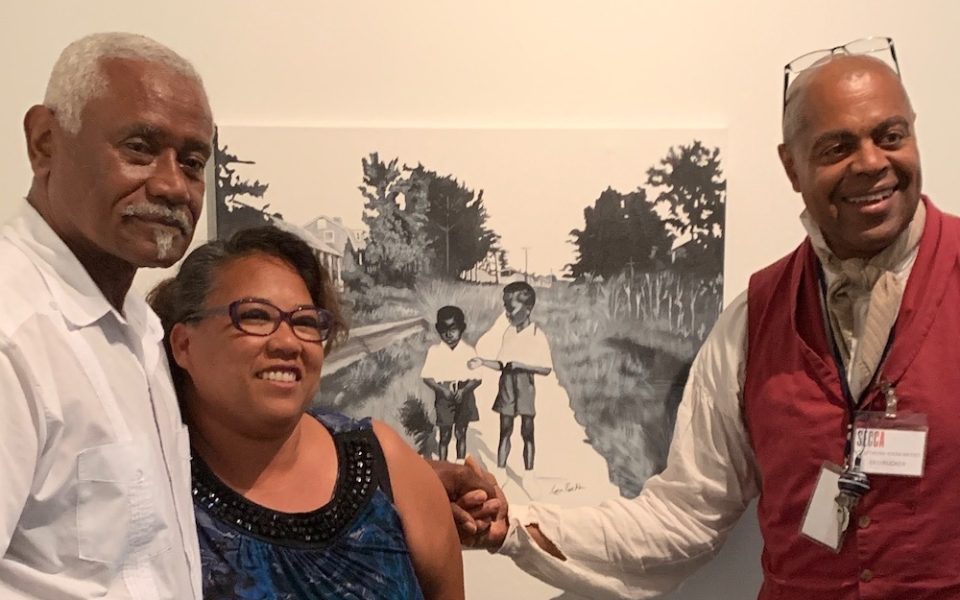

McDuffie, who had six siblings, now lives in Durham and

traveled more than an hour to attend the opening reception for the show last

week.

“How can people care unless they know,” McDuffie asks. “This

exhibition is a resuscitation of a life that was lived.”

In a different corner of the gallery, a young woman looks

longingly out at the viewer, her eyes full of wonder. Beside her, a work in

graphite depicts a man sitting with a girl, perhaps her daughter, each of their

faces lifted ever so slightly with a smile.

-

“We Happy” shows a man and a girl who may be his daughter in graphite. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka) -

In “The Stoneman,” Rucker casts his own interpretation of the protagonists story and personality. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

“She looks like she’s comfortable in his arms,” says Rucker about

the girl in “We Happy.” “I wanted to have a balance. A good mix of men and

women.”

Rucker spent a month deciding which of the 300 or so

archival images he would paint for the show.

“Each one will help us understand that time period,” he

says. “Each one spoke a different conversation to me.”

In “In front of Ms. Mottie’s house,” a toddler reaches playfully towards the camera as they sit in a wooden high chair outside of an old, shotgun-style house. Freshly washed laundry hangs on a line strung along the front porch of a house that sits on a cinderblock foundation. The painting has a quaint feel to it, harkening to a simpler time.

“This was the inner city but it has a rural, country feel to

it,” Rucker says. “I grew up going down dirt roads like this.”

Across the way, a casually cool man stands in the foreground

of a painting entitled, “The Stoneman.” He leans gently to one side as if

caught right before the shot was taken. A tobacco pipe hangs loosely in his

mouth, a mustache protecting his upper lip. According to the original photo,

the man in the picture and painting is John Forney, a local stonemason. Like

many of the other photographs used for the exhibition, not much is known about

those depicted besides their names. That’s why Rucker puts his own spin on

their tales and give them backstories of his own making.

“You can tell he’s strong,” Rucker says as he gazes upon the

painting. “Look at the strong hands. You can imagine him working as a mason.”

Rucker recalls a stonemason from his own childhood named

Robert and projects his personality onto Forney.

“[Robert] was passionate about [his job],” Rucker says. “He

was meticulous. Everything had to be perfect.”

Even without knowing the intimate details of the lives of

those he paints Rucker says that immortalizing them in paint or graphite is

important to keep the memory of Happy Hill alive.

“I want people to think about the paintings,” he says.

“Maybe they can find something that’s relevant or recognize something.”

Despite all of its challenges, Happy Hill continues to be

known for its history and significance in Winston-Salem, and that’s what Rucker

is working to preserve. And for McDuffie and those who still remember the Happy

Hill that once was, it’s enough.

“It’s a joy that you can see and relate to,” says McDuffie,

who continues to visit Happy Hill when he’s in town. “It was joy. You know what

they say. You can take me out of Happy Hill, but you can’t take Happy Hill out

of me. We are spread all over the world, but that is our home. It’s like,

‘welcome home.’”

Painting Happy Hill is on display through Aug. 11. Find out more about the exhibit here.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply