More than one in 10 of the absentee ballots cast in Guilford County so far have been set aside, and an order by a federal judge suggests Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger and House Speaker Tim Moore could ultimately decide whether they get counted.

Almost 17,000 mail-in absentee ballots have been returned in Guilford, North Carolina’s third most populous county, but roughly 2,000 have been set aside because of deficiencies, mainly due to incomplete witness addresses on the envelope containing the ballots.

The unapproved ballots — a limbo status that is neither approved nor thrown out — in Guilford is more than 10 percent the total cast, far exceeding any other county in the state and accounting for roughly a third of all unapproved ballots in the state.

According to data published by the US Elections Project at the University of Florida, 11.7 percent of ballots in Guilford remain unapproved. Rural Scotland County on the South Carolina state line ranks a distant second, with 5.6 percent of ballots unapproved.

Beyond its singular distinction for having the highest number of unapproved ballots in the state, Guilford County conforms to a statewide racial disparity in which ballots cast by Black voters are significantly more likely to be rejected than their white counterparts. Guilford County holds the third largest pool of Black voters in the state, with 123,087 on the rolls, and only in Durham County do Black voters make up a larger share of the overall electorate.

Noting the disparity in Guilford County, Michael P. McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida, wrote in an email to Triad City Beat: “822 African-Americans have had their ballots rejected out of 3,725 mail ballots (22.0 percent rejection rate) compared with 841 whites out of 10,919 returned ballots (7.7 percent rejection rate). I find that very disturbing.”

Statewide, the disparity is even more pronounced, with mail-in ballots cast by African Americans four times more likely to be rejected than those cast by white voters. Latinx and Native American voters are three times and Asians are twice as likely to have their ballots rejected.

Michael Bitzer, a political science professor at Catawba College, said there’s a straightforward reason for that: Historically, white voters have more experience with voting absentee, although that pattern is reversed this year with Democratic constituencies emphasizing safety precautions in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and President Trump maligning mail-in voting. (Bitzer prefers the term “deficient” instead of “rejected” because, at least theoretically, voters with incomplete absentee ballots have the opportunity to fix them so they can be counted.)

“My guess would be that people who have early-voted by mail before probably remember the process,” Bitzer said. “People whose first time it is to vote by mail may not fully understand the instructions. In previous research, voting by mail is an overwhelmingly white method. Black voters are traditionally in-person voters.”

Echoing a point made by Guilford County Elections Director Charlie Collicutt, Bitzer said it’s unlikely that elections staff are demonstrating bias against Black voters in setting aside ballots, because there’s no information about race on the return envelopes.

The Rev. Anthony Spearman, who is the president of the North Carolina NAACP and also a member of the Guilford County Board of Elections, concurred with Bitzer in his assessment for why Black voters are more likely to run into trouble with mail-in absentee ballots.

“Minorities have not been cultivated to use absentee ballots and probably could use some instruction to make sure they do their yeoman’s best to fill out the information correctly,” he said.

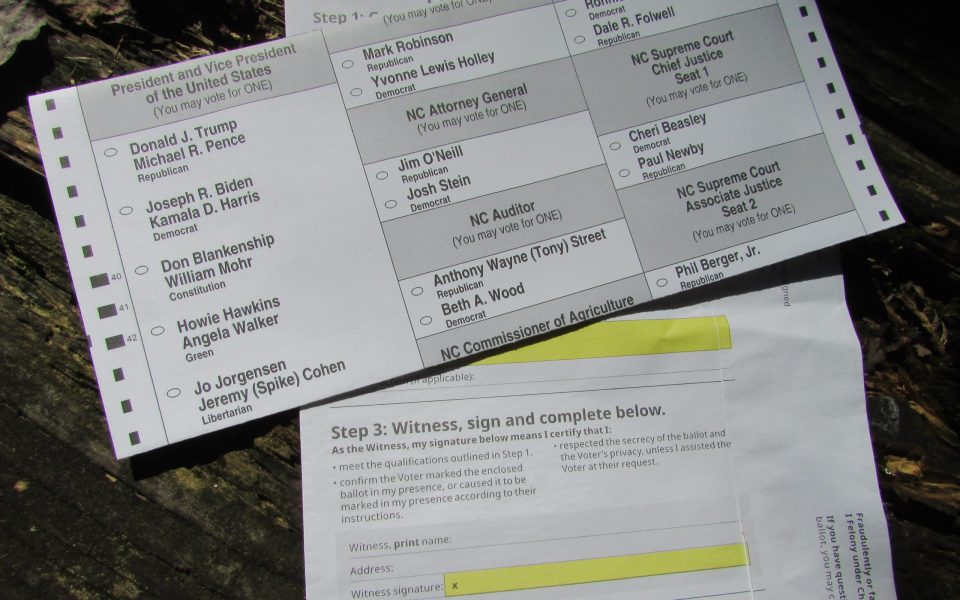

For those who haven’t experienced mail-in absentee voting, the most unfamiliar aspect is likely to be the return envelope, which requires not only the voter’s signature, but the name, address and signature of a witness.

“We’re continuing in all of our messaging to emphasize how important it is to complete that envelope with the information that it asks for,” Spearman said of the NAACP’s voter education outreach. “Don’t settle for just putting in your address. Make sure you have the city and the ZIP code.

“One of the things we’re pushing is to get their absentee ballot in as soon as they can,” he continued. “If there are any problems with the cure process, I would want them to have time to deal with that. People need to get those in as soon as possible. Don’t use the mail; take them in to the county board of elections office.”

Collicutt said that “by far what’s driving” the high rate of unapproved ballots in Guilford County is missing information in the line for witness addresses. Typically, the return envelopes for the deficient ballots display a street address for the witness on the return envelope, but are missing the city, state and ZIP code.

“If you look at voter’s missing information or they didn’t provide an address at all, our percentage drops down to 3 percent, which is more in line with other counties, Collicutt said.

To determine whether ballots are acceptable, county elections staff are relying on a document known as NC Board of Elections Memo 2020-19, which was issued by the state Board of Elections on Aug. 19 and then revised on Sept. 22. A footnote on Memo 2020-19 explains that “failure to list a witness’s ZIP code does not require a cure,” but that “if both the city and ZIP code are missing, staff will need to determine whether the correct address can be identified.”

But Collicutt said local elections directors haven’t received any guidance on what research methods they should take to ascertain that an address is indeed a valid Guilford County residence or to deduce whether an address is in, say, Greensboro or High Point.

“I’m asking the state Board of Elections: ‘Should I Google this person?’” Collicutt said. “Is that permissible? I don’t know what other counties are doing. I think there’s a hodgepodge.”

Collicutt emphasized that if the state Board of Elections gives him guidance that his staff can exercise more discretion, he can still move the deficient ballots into the approved pile.

“If we’re wrong, this is fixable,” he said. “They’re not being destroyed or thrown in the trash. They’re locked in a vault.”

The state Board of Elections could not be reached for comment for this story.

Meanwhile, Memo 2020-19, which contains the clearest guidance on how local elections staff should handle deficient absentee ballots, has landed at the center of a thicket of lawsuits, with Republican legislators charging that the state Board of Elections is illegitimately encroaching on its lawmaking authority and a host of voting rights organizations like Democracy North Carolina and the League of Women Voters of North Carolina fighting to ensure that all ballots are counted. The memo has also landed in the crosshairs of the Trump campaign.

What’s specifically in dispute in Memo 2020-19 is a provision allowing voters to cure ballots that are missing a witness signature by signing a certification.

Joshua Stein, North Carolina’s Democratic attorney general, is representing the state Board of Elections in the case. In a legal filing submitted to US District Court Judge William Osteen on Friday, Stein cited reporting by FiveThirtyEight raising the alarm that Black voters’ absentee ballots were being rejected at more than four times the rate of white. The FiveThirtyEight report, published on Sept. 17, was the first to show that Black voters were being disproportionately impacted, and the University of Florida data shows that the pattern remains unchanged two weeks later.

Even before voting got underway in early September, state election officials were anticipating a 10-fold increase in mail-in voting, Stein wrote, and the original Memo 2020-19 was intended to allow voters the opportunity to correct problems with their absentee ballot. Primarily, the original memo addressed problems with the voter signature, and Stein wrote that “the original cure memorandum appeared to result in unintended consequences of disproportionately rejecting the ballots of voters of color” and “may, unwittingly, have contributed to the deprivation of the right to vote for specific protected groups within North Carolina’s voting population.”

Karen Brinson Bell, the executive director of the State Board of Elections, noted the same thing.

“After issuing the original memo, we also received reports from numerous sources reporting that there was a disparate impact on African-American voters,” she wrote in a declaration filed with Judge Osteen on Friday. “These voters were more likely to have their ballots rejected. I became concerned that the original cure memo did not adequately address this issue. State Board staff began seeking ways to address these concerns within the existing legal framework.”

North Carolina is uniquely marred by election fraud through absentee ballots: The 2018 9th Congressional District election was thrown out by the State Board of Elections after a ballot-harvesting scheme came to light benefitting Republican candidate Mark Harris.

Earlier this year, the General Assembly passed bipartisan legislation reducing the required number of witnesses for an absentee ballot from two to one in light of the safety concerns of voting in person due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the burden of finding two witnesses.

Explaining her reasoning for instructing local election staff to allow voters to correct missing witness signatures by “attesting that he or she voted their ballot and is the voter,” Bell said in her declaration to Judge Osteen that “the purpose of the witness requirement is to prevent the voter from having their ballot stolen and marked without their knowledge, and the cure certification would provide a second contact with the voter to ensure this improper activity had not happened.”

Bell said in her declaration that she learned on Sept. 25 that Heather Ford, identified as “the NC Election Day Operations director for the Donald J. Trump for President campaign,” had emailed Republican members of the county boards of elections and “advised them not to follow the procedures outlined in Numbered Memo 2020-19.” Bell said that in response the State Board of Elections’ general counsel emailed all 100 county boards of elections with instructions “to follow all processes” in the memo.

But on Thursday, Bell had to reverse course in response to an order from Judge Osteen expressing concern that Memo 2020-19 amounts to “elimination of a duly-enacted statute requiring a witness to an absentee ballot.” She issued a new memo ordering county elections boards to secure absentee ballots missing the witness signature pending further direction from the court.

Osteen has scheduled a status conference for Oct. 7 in federal court in Greensboro. He asked the State Board of Elections and the Republican lawmakers to preview their arguments.

In a response filed on Friday, Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger and House Speaker Tim Moore asked Judge Osteen to uphold the Bipartisan Elections Act of 2020 by requiring that “all absentee ballots must be witnessed by one person who is at least 18 years old,” while arguing that “allowing a voter to ‘cure’ a missing witness signature in any way other than spoiling the deficient ballot and issuing and new one would serve as an end-run around this requirement.”

The State Board of Elections is taking the position that Memo 2020-19 “does not improperly eliminate the witness requirement.”

“If a voter makes an error with regard to the witness requirement, the voter is able to cure her ballot only by taking extra steps that she would not have had to take if she had met the witness requirement,” Stein wrote on behalf of the State Board of Elections. “The same is true of the voter signature requirement — where a voter makes a mistake with the voter signature requirement, the voter is able to cure her ballot only by taking extra steps that she would not have had to take had she met the voter signature requirement. For the voter to complete these extra steps, the county board of elections must reach out to the voter, separately and directly, using the contact information the voter provided in her absentee ballot request form, and provide a cure form directed specifically to that voter. The voter must then attest that she is the one who marked her ballot by returning a separate certification, fulfilling the purpose of the witness requirement.”

Hours after receiving responses from the State Board of Elections and the Republican legislators on Friday, Osteen issued a new order late Friday afternoon seeking additional motions from the parties. But the order telegraphs Osteen’s constitutional view, presaging a potential judicial justification for North Carolina’s Republican-controlled legislature to appoint Trump-friendly electors in the event of a disputed election.

In a rebuke to the State Board of Elections in the role of “executive defendants,” Osteen wrote, “As the Supreme Court has explained, it is the legislature, not the state executive body, that establishes the rules of the election process.”

Then, the federal judge, who was appointed to the bench in 2007 by President George W. Bush, quoted from Bush v. Gore, the Supreme Court split decision that threw the 2000 election to Bush.

The ruling, as quoted at length by Osteen, outlines that the power of the people to elect the president is not absolute, and the state legislature can wrest it back.

“The individual citizen has no federal constitutional right to vote for electors for the president of the United States unless and until the state legislature chooses a statewide election as the means to implement its power to appoint members of the electoral college,” the ruling reads. Bush v. Gore goes on to cite the principle as the source for a finding in an 1892 case, known as McPherson v. Blacker “that the state legislature’s power to select the manner for appointing electors is plenary; it may, if it chooses, select the electors itself, which indeed was the manner used by state legislatures in several states for many years after the framing of our Constitution.

“History has now favored the voter, and in each of the several states the citizens themselves vote for presidential electors,” Bush v. Gore continues. “When the state legislature vests the right to vote for president in its people, the right to vote as the legislature has prescribed is fundamental; and one source of its fundamental nature lies in the equal weight accorded to each vote and the equal dignity owed to each voter. The state, of course, after granting the franchise in the special context of Article II [of the Constitution], can take back the power to appoint electors.”

Bush v. Gore then quoted from a passage in a report made by the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections that eventually made its way into the McPherson decision: “Whatever provisions may be made by statute, or by the state constitution, to choose electors by the people, there is no doubt of the right of the legislature to resume the power at any time, for it can neither be taken away nor abdicated.”

UPDATE, Oct. 5, 3:31 p.m.: The NC Board of Elections issued a new numbered memo on Sunday providing guidance to assist local elections staff in handling mail-in absentee ballots with missing witness address information. In the event that the ZIP code and city is missing on the address line for witnesses, the guidance directs elections staff to approve the ballots if the witness address is the same as the voter’s address; if the witness’ address matches the address of a registered voter in the county; or if it matches a valid address in the county GIS website.

Guilford County Elections Director Charlie Collicutt said his staff has worked through about half of the pile of “deficient” or “rejected” ballots, and the rate of deficient ballots compared to all returned ballots has dropped from 11.7 percent to about 6.3 percent.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply