The lines cut deep into the faces of the protagonists, weathering them, signifying years of lived experience with each groove — years of oppression, resistance, resilience.

The faces that peer out from the frames are part of a new art exhibit in Greensboro that features work by members of Taller de Gràfica Popular, a Mexican social-justice art collective that spoke truth to power through prints during the mid-20th Century.

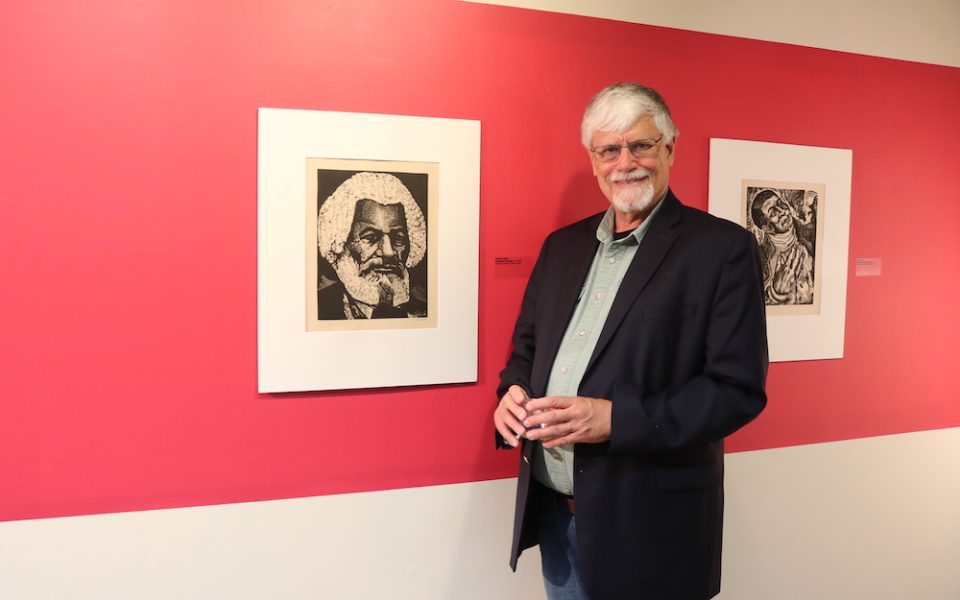

Engraving Injustice opened at the beginning of June in the African American Atelier gallery in the Greensboro Cultural Center and is presented by Casa Azul. The exhibit features close to 50 prints collected by Robert Healy, a Duke environmental-policy professor and avid print collector.

“I have always like art with some sort of message,” Healy says. “Work for not merely aesthetically pleasing aspects but also to express some thought or emotion or political emotion and I think that’s what the TGP does very well.”

Healy began collecting prints by the TGP during his travels to Mexico for work. Soon he found himself seeking them out each time he visited, eventually befriending the printer and some administrators in the group.

Taller de Gràfica Popular was founded in 1937 by three artists — Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins and Luis Arenal — in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution as a way to further the ideals that came about during the previous two decades. In its heyday, through the 1960s, the collective — which translates to “The People’s Graphic Workshop” — boasted about 40 members and produced thousands of prints, mostly linocuts and woodcuts that were inexpensive and whose materials were easy to obtain. Rather than producing work for galleries, the artists printed images on whatever they could find: newspapers, posters, cards that could be handed out or displayed in the streets. The collective was open to anyone who wanted to be an artist regardless of nationality or social class and worked to lay bare a variety of social-justice issues such as the exploitation of the poor and peasant rights. They criticized European fascism and imperialism from the United States. A series of prints in the beginning of the exhibit, some by prominent black American artist Elizabeth Catlett, features portraits of significant African Americans like Crispus Attucks, Frederick Douglas and George Washington Carver.

“The workshop was one of the first self-supporting artist workshops,” says Mariana Rodriguez, the artistic director and co-founder of Casa Azul. “They created and published their own work. They did a lot of satire work and used social justice as a way of informing the community about things that were going on.”

The works focus on the human condition. The heroes in the foreground represent the common people who resist authority. A woman with jet-black hair cradles power lines and a smoking factory, whose pollution empties out into a body of water that serves as a home to a pair of fish. A man boldly stands in front of a line of guns that point at him while a crowd of people lurk in the background. A young African-American boy makes unyielding eye contact with the observer as he unshackles the chains that encircled his wrists. Revolting slaves with weapons assemble behind him.

-

The TGP tackled social justice issues that relate to environmentalism, worker’s rights, and uplifting the poor. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka) -

The TGP worked as a collective and often just signed their pieces, “TGP.” (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka) -

In addition to uplifting Mexican people’s rights, the TGP made several prints relating to African-American liberation and rights. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

The prints, despite being mostly black and white, prove powerful and moving. Made decades ago, in a vastly different political climate and country, the images have the power to evoke emotions because of their current relevance.

The woman cradling the industrial complex reminds viewers of the ongoing injustice in Flint, Mich. The man confronting the soldiers echoes the current protests in Hong Kong. The young black boy looks harrowingly like Trayvon Martin.

They serve as a reminder of how far we’ve come but also how far we’ve yet to progress.

“We decided that it was absolutely necessary to show this exhibit now,” Rodriguez says. “It felt like it was the right context to show it in a place like Greensboro. The city is looking for ways to learn about their own communities, maybe the Latino communities. We think the community would really benefit from learning about Mexico’s history.”

Healy expressed agreement and lamented the rampant xenophobic rhetoric against the Latino population in politics these days.

“I have a real reason for wanting to display this art at this time,” he says. “In the last 25 years or so, the Latino population… has increased from 0 to 10-15 percent of the population. I think that North Americans don’t appreciate the richness of Mexican culture. People may like taco trucks and Cinco de Mayo… but this is only a tiny part of what is one of the world’s greatest cultures.”

While the collective is no longer active, the TGP’s legacy and messages continue to live on through its work.

“Their work is didactic,” Healy says. “I want people in Greensboro to have a chance to enjoy this but also learn from it.”

Healy will give a talk about the work on Friday from 7-9 p.m. Engraving Injustice is on display at the African American Atelier through Aug. 2. To learn more, visit the Casa Azul website here.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply