This story was originally published by NC Policy Watch on Dec. 15. Story by Lynn Bonner.

State legislators will soon get another look at a plan aimed at improving maternal health in North Carolina, with a request to provide better pay to health care workers who provide maternity services to people enrolled in Medicaid, reimburse for doula services, and increase payments to providers of group prenatal care.

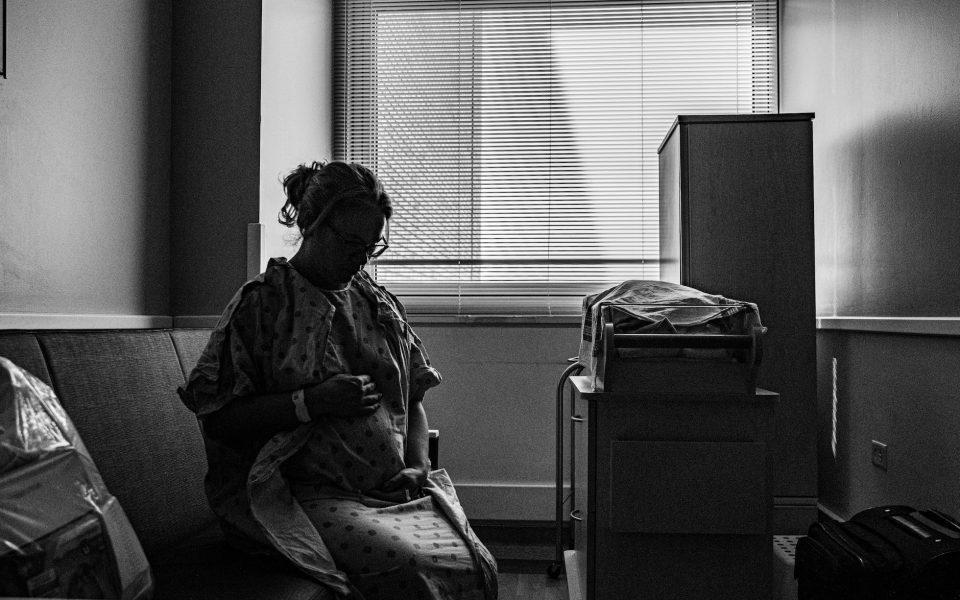

The United States has the worst maternal death rate among industrialized nations, and Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women.

Meanwhile, North Carolina has one of the worst infant mortality rates in the U.S., according to the CDC, with Black babies more than two and a half times as likely to die before their first birthdays as white infants. Babies in North Carolina are more likely to be born underweight than babies born in most other states. Preterm birth/low birth weight is a leading cause of infant death, according to the CDC.

Gov. Roy Cooper suggested these changes to improve maternal health in his budget proposal this year, but the legislature did not support the increases. A permanent legislative study commission known as the Child Fatality Task Force voted this week to support the package of changes. The total cost would be $27 million per year, according to information provided to the task force, but because the federal government pays most of the bill, the state’s costs would be about $9 million per year.

Doulas can make a big difference

State officials and maternal health care professionals have been thinking for years about adding North Carolina to the group of states that allows Medicaid payments for doula services. Doulas provide physical and emotional support during labor and childbirth. Some doulas meet with parents beforehand and after babies are born.

Births attended by doulas are two times less likely to have complications for mothers and babies, according to a 2013 study. Mothers who receive doula support are also less likely to have a cesarean section, more likely to have babies born at healthy weights, and more likely to breastfeed. C-section rates for Black women are higher than for white women. Studies have reported that doulas help reduce the impact of racial health care disparities and racial bias.

“We know that patients who are insured by Medicaid need to have access to doula services,” said Tina Sherman, senior campaign director for MomsRising Together and the MomsRising Education Fund.

A few of the state’s Medicaid managed care plans offer limited doula services, but they are not widely available. Most private insurance plans do not cover doula services, so a vast majority of parents who hire them must pay out of pocket.

“As a public policy advocate and a public health advocate, we really need to be educating lawmakers and decision makers how doulas can fit into an overall effort to address maternal health,” she said.

While nursing shifts can change during labor, the doula is there to provide continuous support.

“The doula is with the birthing person the entire time,” Sherman said.

Doulas aren’t a panacea, she said, but are part of the solution.

A summit this year gathered doulas from around the state to consider what a Medicaid-funded doula service might look like. Attendees also heard reports from three states that include doula services in their Medicaid plans. Sixteen states curentrly reimburse doulas through their Medicaid plans or plan to start, according to the National Health Law Project.

One piece of advice from other states was to engage doulas early, said Belinda Pettiford, chief of Women, Infant and Community Wellness at the state Division of Public Health. ‘You don’t want to build it and assume people will come,” she said.

Health officials are continuing to meet with doulas and will have a report on their findings next month, she said.

“One of the things we’ve heard from other states and doulas themselves is it’s a type of position you can burn out in,” Pettiford said. “You’re on call when the pregnant person needs you.” Because of the limits connected to an on-call profession, “you have to have a back-up system.”

Group prenatal care

In recent years, some maternal health providers have offered group prenatal visits for expectant parents, in which individuals receive check-ups privately, then meet as a group to talk about their experiences with pregnancy, exchange ideas, and ask questions.

Some types of group prenatal care have been shown to reduce the risk of pre-term birth, and lower the risk of having underweight babies. Some studies also show the racial gap in preterm birth rates is reduced.

Medicaid pays for group prenatal care, but the recommendation for increased payments recognizes additional cost to providers, said Michaela Penix, North Carolina director of maternal and infant health for the March of Dimes.

“The reality is, Medicaid reimbursement is already low,” she said.

The March of Dimes supports group prenatal care at two North Carolina sites, including the Cumberland County health department, with the help of Blue Cross Blue Shield, she said.

Providers are asked to provide snacks for parents, and some purchase additional equipment, Penix said.

The group meetings help build camaraderie, Penix said, and provide “a level of support to maintain a healthy pregnancy.”

That support is particularly important in military communities such as Cumberland County, where partners may be deployed overseas, she said.

About one-fifth of the state’s 100 counties don’t have obstetrician/gynecologists, OB/GYN physician assistants, or certified nurse midwives, according to a state analysis.

Forty-one percent of births in the state were financed by Medicaid in 2020, according to Kaiser Family Foundation. But providers of maternity care for Medicaid patients don’t make as much as medical professionals in other states doing the same thing. Virginia and Georgia are among the states with better Medicaid rates for maternity care.

As the state tries to recruit a medical workforce for maternity care “we need to do what we can to get that rate increased,” Pettiford said.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply