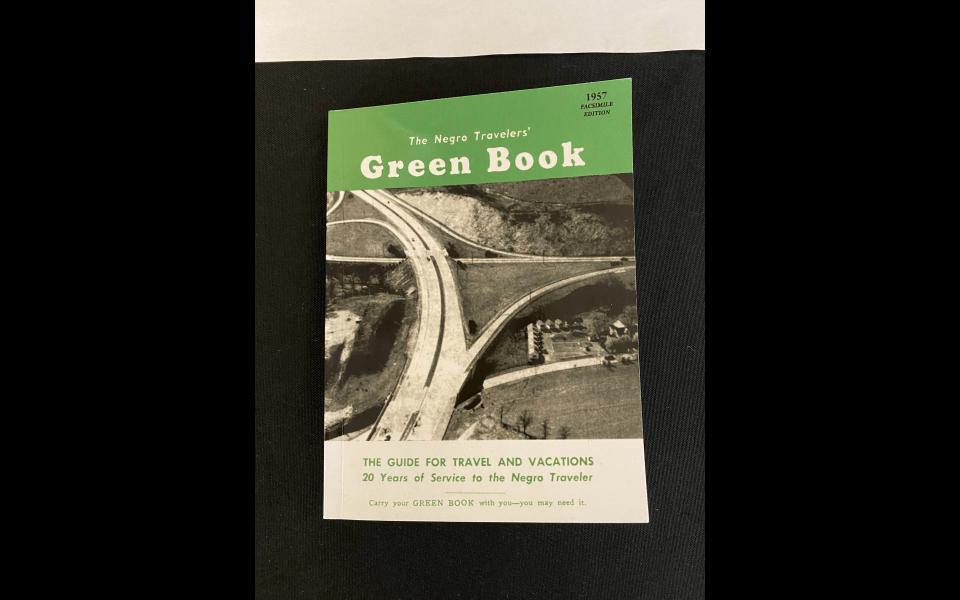

Featured photo: An old Green Book on display at an exhibit in Winston-Salem (photo by Michaela Ratliff)

The lump in my throat grew larger and my eyes welled with tears as I turned the pages of a 1938 edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book. I stood alone in near-silence, disturbed only by the sounds of jingling car keys dangling from the lanyard around my neck and the buzzing of suspended panel lights above me. I had never touched a Green Book before this, but I was aware of its existence and what it represented during its circulation: strength, perseverance and a sense of community among Black travelers of the 20th Century.

The Green Book, known as the “Bible of Black Travel” was published by postal worker and travel writer Victor Hugo Green from 1936-67 and was a guide for Black travelers, showing them more than 300 restaurants, hotels, beauty salons and other businesses they could safely patronize during the era of Jim Crow.

Navigating Jim Crow: The Green Book and Oasis Spaces in North Carolina — on display at the Enterprise Center in Winston-Salem until Nov. 18 — is a traveling exhibit curated by the NC African American Heritage Commission. Presented by Triad Cultural Arts, the exhibit features information boards, physical copies of the Green Book and an interactive story map with photos and newspaper clippings involving 18 Winston-Salem businesses listed in the Green Book.

The unassuming exhibit sits on the first floor of the Enterprise Center and features two water fountains displaying “Whites Only” and “Colored Only” signs, similar to the ones Black travelers may have seen in certain businesses. Touch-screen monitors displaying a website highlighting Winston-Salem Green Book sites and take-home resources for visitors including a Green Book word find and list of additional resources for reading sit on nearby tables. Each table possesses a different version of the Green Book, published as The Negro Motorist Green Book from 1937-1951, The Negro Travelers’ Green Book from 1952-1959, and The Travelers’ Green Book from 1960-1966. There is also a Magnolia’s Shoebox Lunch from the Historic Magnolia House on each table, reminiscent of the shoebox lunches Black travelers would carry on their routes. While none of the Winston-Salem Green Book locations are left standing, a take-home picture booklet provides photographs of the sites.

The interactive story map spotlights 18 Green Book locations in Winston-Salem and compares some to the area’s present-day appearance.

According to the story map, the Belmont Hotel at 601 ½ N. Patterson St. was listed in the book in 1952, 1953 and 1954.

“The two-story, brick building stood on the north side of Sixth Street between Patterson Avenue and Vine Street, where the parking lot north of Biotech Place is located today,” the map reads.

Orchid Beauty Salon at 619 E. Ninth St. was listed in the book in 1938. The open space formed by the ramp that takes traffic from Martin Luther King Drive to US 52 southbound is where the salon once stood.

“Stinson’s Service Station at 1012 E. Fourteenth St. was listed in The Travelers’ Green Book in 1961,” the description reads. Today, the location is occupied by residences along 1100 and 1112 E. Fourteenth St.

Eight panels located across the room display photographs and information about Green Book locations across the state in Raleigh, Wilmington and Asheville and important figures from those cities.

Gazing upon the Green Book, I found myself filled with emotion as I placed myself in the shoes of my maternal great-great grandfather Isaac M. Powers. He was born into slavery and later became the first Black landowner in Duplin County after emancipation, some land of which my family still owns today. Mesmerized, I read the same words Isaac possibly did as he roadtripped the state before and during the Jim Crow era ministering at churches, working in politics and even eulogizing Booker T. Washington at the 1915 NC Colored Baptist State Convention.

“There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published,” the introduction of an online 1949 edition of the Green Book reads. “That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States.”

It continues, “It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment. But until that time comes we shall continue to publish this information for your convenience each year.”

Each reader was encouraged to stay alert in new areas, spread word of the book to businesses and to keep it on them at all times.

“Carry your Green Book with you — You may need it,” the front of nearly each copy says.

The Isaac M. Powers House in Wallace, NC, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was constructed around 1878 near the beginning of the Jim Crow era. Like the Winston-Salem Green Book locations, the house no longer stands. It’s unknown if the house was a Green Book site; however, the gathering of Powers’ descendants for a family reunion each September near the house’s land is reminiscent of Black traveler’s enjoying safe havens they found using the Green Book. “Oasis spaces” where they could exist undisturbed, happily and Black.

The impact of these locations and the warmth, comfort and most importantly, safety they provided can still be felt just by visiting or reading about the areas today.

Learn more about Navigating Jim Crow: The Green Book and Oasis Spaces in North Carolina, the African-American Heritage Coalition and Triad Cultural Arts at bit.ly/WSGreenBook, aahc.nc.gov/green-book-project and triadculturalarts.org. Oasis Spaces is on view at Enterprise until Nov. 18.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply