Greensboro residents have received little to no information about plans for the next cycle of participatory budgeting. And despite differing perceptions among both advocates and city council members, the program has effectively been expanded from a 1-year to 2-year cycle, halving the amount of money allocated to implement projects.

In October 2014, Greensboro became the first city in the South to adopt participatory budgeting, a process in which the city carves out a slice of the budget, while allowing residents to propose and vote on projects.

The amount for each funding cycle — $500,000 — was miniscule, as Wayne Abraham, a proponent acknowledged.

“What could be better than the citizens of Greensboro becoming involved in their own government and helping to decide how to spend one-tenth of 1 percent of their own money?” Abraham asked.

The project was adopted on split 5-4 vote, with Mayor Nancy Vaughan joining three other members in opposition. The other opponents, including Zack Matheny, Mike Barber and Tony Wilkins, have either retired or lost their re-election bids.

The proposal forced a debate about the nature of democracy. Vincent Russell, another proponent, posited one view: “Our democracy is based on the idea of electing representatives to make the tough decisions for us.

“But for others of you, like me, we understand that democracy is bigger than this narrow definition,” Russell said. “We understand that democracy requires an informed and engaged electorate. We know that democracy means listening to everyone’s voice, and helping foster a sense of community. For those of you like me, we know that democracy means one person, one vote. And it means empowering people to make decisions for themselves.”

As Durham, a smaller but more economically dynamic city to the east, prepares to launch its own participatory-budgeting project, implementation in Greensboro has slowed to a crawl and low participation in the first two cycles has matched the modest allocation. In the first cycle 1,123 residents voted, while 1,199 voted in the second cycle. In comparison, 29,697 people voted in the 2017 Greensboro mayor’s race — an anemic turnout that was itself only 14.7 percent of the electorate.

And while Greensboro has effectively halved the already small allocation of $500,000 by funding the program every two years instead of every year, Durham City Council adopted a more ambitious project on May 21, voting 7-2 to adopt a budget of $2.4 million.

The current status of the Greensboro participatory budgeting project has been a source of confusion among both advocates and council members. The staggered scheduling of public input phases on one hand and funding phases on the other has effectively resulted in the project — at least for now — morphing from a 1-year to a 2-year cycle. As the program’s fourth anniversary approaches, its relatively brief history is complicated: Residents generated ideas and voted on projects during the first cycle from the fall of 2015 through the spring of 2016. The first cycle was funded in the fiscal year 2016-2017 fiscal budget adopted by city council. Then the beginning of the second cycle of idea generation and voting was pushed back six months, beginning in March 2017 and concluding with voting in October and November of that year. Funding for the second cycle is included in the proposed fiscal year 2018-2019 budget expected to be adopted this month. Jason Martin, a budget management analyst for the city, and Councilwoman Marikay Abuzuaiter said the next ideal collection phase will begin in spring 2019.

Some council members, including Abuzuaiter and Mayor Pro Tem Yvonne Johnson, have said they want to see the city move to funding participatory budgeting every year instead of every two years, but it remains unclear whether there are the five votes needed to assemble a majority and make it happen. No council members interviewed for this story were aware of any plans to bring the measure up for a vote.

“Personally, I would love to get to the point where we can fund it every year, but I don’t think the council has officially stated that is the way it will be going forward,” Councilwoman Tammi Thurm said.

Audrey Berlowitz, an early advocate for participatory budgeting who promoted the initiative in the run-up to the 2014 vote for adoption, waited for word of a new cycle of idea collection as March, and then April and May came and went. The page for the current participatory budgeting cycle on the city’s website says only: “The city of Greensboro is currently in the planning stages for PB Cycle 3. Please return to this section for information about Cycle 3 as it develops.”

Berlowitz said she was disappointed to learn that the cycle has been stretched into two years with little to no public communication from the city to residents.

“People feel so disempowered,” Berlowitz said. “It’s so hard to talk about how to be a citizen. Citizenship is considered kind of a joke. Participatory budgeting is this small, little thing that could begin to engage people. It’s disheartening to me that this small, little thing — participatory budgeting — is disregarded. We as citizens have to hold our government accountable, so it’s just as much on us.”

Berlowitz added that she worries that by shifting the public input component of the program from once a year to once every two years, participation will only diminish because residents will forget about it.

Thurm acknowledged the challenge.

“I’d like to keep the momentum so we can educate and build and keep things moving forward,” she said. “That’s very difficult to do on an every-other-year basis.”

Wayne Abraham, the chair of the Participatory Budgeting Steering Committee, said in statement to Triad City Beat that participatory budget “was originally discussed” with city council and staff “as being done annually.”

Councilwoman Sharon Hightower — who voted with the majority to adopt participatory budgeting in 2014, along with Yvonne Johnson, Marikay Abuzuaiter and Nancy Hoffmann — defended the 2-year funding cycle, arguing that it’s necessary to prevent implementation of projects from falling behind.

“Ideas are being generated every year,” Hightower said, despite the fact that the last idea collection took place in 2017 and the next one isn’t scheduled until 2019. “PB is an every-year engagement process; it’s just not funded every year.” Hightower and Abuzuaiter said ideas generated in years when there is no money allocated in the participatory budgeting program budget could be funded through the city’s general fund, or moved up in the capital improvement project budget if there’s a public safety justification.

“Council may choose to do it annually or bi-annually,” Abraham said, adding that the citizen steering committee would “work within the parameters council creates.”

Abraham said the steering committee “is currently working to make Round 3 even more successful than Rounds 1 and 2. We anticipate becoming a formal city commission in the near future. We are going to create benchmarks to ensure that we reach all parts of the city and that we increase participation to an even higher level. We are currently working on making online voting available and partnering with more groups in the city.”

Abuzuaiter said she frequently encounters residents who haven’t heard about participatory budgeting.

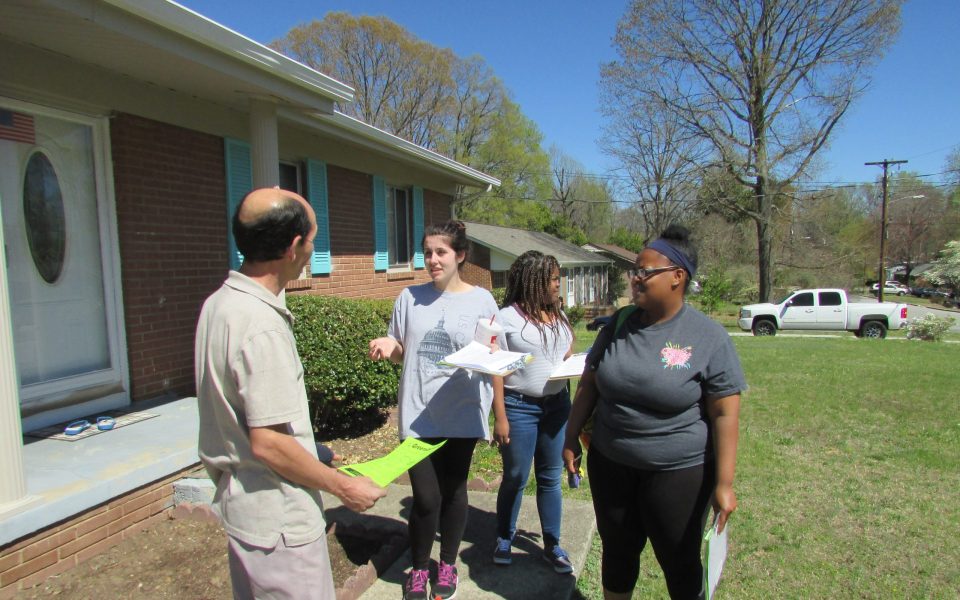

“We’re trying to get the word out to communities that may not be on social media,” she said. “A lot of it is going to be word of mouth: ‘Have you heard about participatory budgeting?’ When I talk to community groups, they’re excited about it.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply