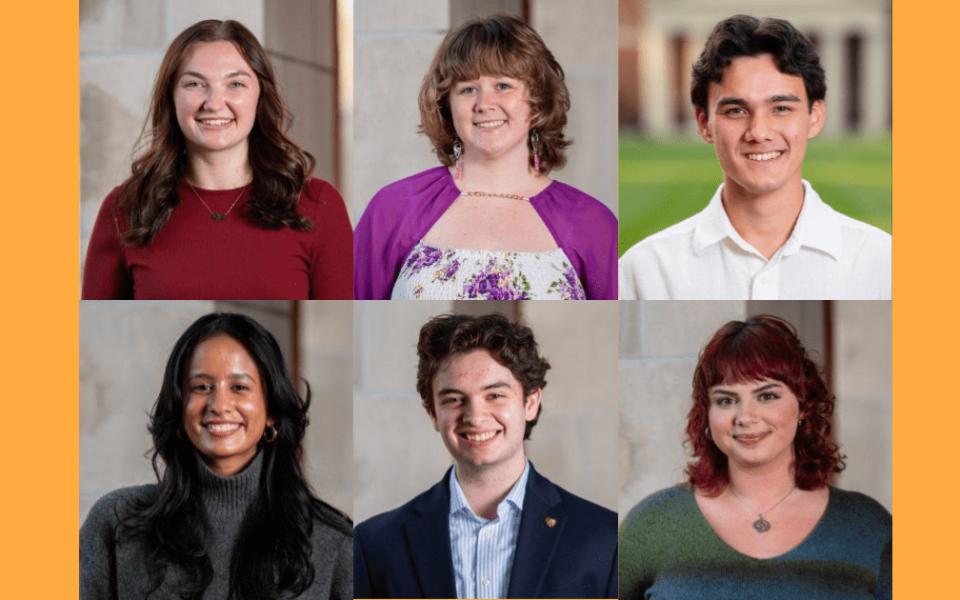

Featured photo: Members of the Old Gold and Black who led the coverage of the pro-Palestine protests at Wake Forest University.

“All hands on deck.”

That’s how rising senior and Editor-in-Chief Maddie Stopyra describes how the newsroom of the Old Gold and Black, Wake Forest University’s student newspaper, came together the day they found out about pro-Palestinian protests that began on campus on April 30.

For the next four days, members of the paper found themselves reacting quickly to cover the subsequent protests, encampment and negotiations between students, faculty and administrators. They slept very few hours during those four days.

“It was a blur,” says rising junior and Environment Editor Ella Klein. “I don’t remember leaving [the encampment]. I maybe remember going to my bed.”

In the wake of mass protests that have cropped up on university and college campuses across the country, student newspapers have filled the gap and provided important, timely and contextual coverage in a way that many mainstream media have not been able to. Despite being less experienced, these journalists have the capability to be on campus in the middle of the action, close to the events.

In recent weeks, many organizations, from the Pulitzer Prize Board, which recognized “the tireless efforts of student journalists,” to the Nieman Lab, which interviewed student editors across four different papers, have highlighted the work of these newspapers.

“Student journalism is like the most hyperlocal journalism that you can do except for really small-town journalism,” says Phoebe Zerwick, the director of journalism at Wake Forest University and the paper’s faculty advisor. “That makes it really challenging.”

As the minutes turned to hours, the staff quickly pivoted to ensure that the most accurate information was getting out to the wider campus community. To that end, instead of writing up individual stories, Stopyra made the executive decision to cover the protests as a live feed. The result was a constantly updated story that lived on the Old Gold and Black website, as well as updates that were posted on the paper’s social media platforms.

“There’s an underappreciated weirdness to covering these kinds of protests on small campuses,” says rising junior and City and State Editor James Watson. “Other schools have tens of thousands of students; we don’t have that. I think it ingrained in us an almost guilt reflex to stay there as long as we did to make sure that someone is there to watch, that nothing terrible was happening.”

While the core group of reporters who covered the protests last month had never done protest coverage before, they had grown accustomed to the urgency of breaking news, thanks largely to the pandemic.

“The pandemic really increased the sense of urgency among student journalists in their role,” Zerwick explains. “The week that campus shut down, it was spring break; I was out of town. And even before they consulted with me, [the paper] was publishing updates online about the pandemic and they didn’t stop.”

Soon, faculty and staff were relying on the paper for up-to-date information in the way that they might have previously done with the local daily.

“That was a turning point in students seeing that in their peers, that the entire campus community was relying on them for reliable information,” Zerwick says.

So when the protests started and Stopyra started getting notifications on her phone from friends and colleagues, she had a plan for action. She sent a text message to the executive group — made up of herself, Deputy Editor Shaila Prasad, Managing Editor Breanna Laws and Multimedia Director Evan Harris — and the group made a plan of who was going to cover what. In the beginning, Stopyra had planned to write a bulk of the story, but as they shifted to doing live updates instead, she found that the workload was too much for one person. That’s when her colleagues helped balance the load. Prasad, Watson, Laws and Klein stepped in, often staying at the encampment for hours on end, taking notes, doing interviews and writing updates. When one of them got too tired to continue on, another would tap in.

“We developed a check-in system that allowed us to continue updating our readers without burning ourselves out, which ultimately made the story better,” Laws says.

And the help didn’t end with just the work of making news.

“The skill of knowing when to show up with snacks cannot be undervalued,” jokes Watson, who brought Nerds gummy clusters at a pivotal moment.

“He was like an angel,” Klein says.

But it wasn’t about just one person swooping in to save the day. Throughout the conversation, the six staffers who contributed to the story consistently bring up the importance of sharing the burden.

“It was important to know when to ask for help or knowing when you need to see someone to tell them they’re doing a good job,” Watson says.

The other reason why checking in was so important was because of the difficult subject matter. None of the members had ever covered a protest, particularly one that involved their own peers. And that proved more difficult than they realized.

“I think the hardest part was that it’s such a small school,” Klein says. “I had a relationship with people on both sides; it’s such a small space so it’s easy to feel like you’re in the eye of a hurricane and the storm is moving around you.”

That kind of contentious environment is a difficult one to navigate, especially in heightened political tensions, the journalists said.

Perhaps the individual that had the hardest time was Harris, who had the responsibility of photographing the protest. With the issues of doxing, social-media bombardment and potential backlash from school administration, the job of taking photos became an increasingly fraught one.

“The toll that this can have on your well-being should not be dismissed,” Laws says. “I think it’s hard to be a journalist in today’s climate….”

“There were times when I was given a hard time and I had to think about compromising people’s identities,” he says. “That was difficult because Wake is a really small place; we know all these kids; we will see them in the fall. I don’t want to hurt anybody, but at the same time, it’s our campus, and it’s our job to bring the information to the readers.”

In order to maintain their credibility and show both protesters and counterprotesters that they were just there to do their jobs, all of the members of the team wore their newly created press credentials while out reporting.

“Our responsibility was to tell what happened and try to put it in context and I think we did,” Stopyra says. “And sometimes we had to take a step back and do more research and give more context.”

But this generation of journalists doesn’t adhere to the idea of objectivity in the same way that past generations do. Zerwick says she’s stopped teaching the concept in her classes altogether.

“I don’t really teach objectivity anymore,” Zerwick says. “What I teach is an objective method. I teach that we all need to be aware of our biases; I teach fairness; I don’t teach balance anymore. I teach multiple points of view instead of this idea of two sides.”

That comes directly out of conversations from the Black Lives Matter movement of 2020. And it’s having an impact on the student journalists.

“I’ve gone on the record saying that objectivity is an unreasonable standard,” Klein says.

What they want to center their stories on instead is empathy, Stopyra explains.

“We need to do our jobs, and we need to report on our campus as well as we can, but at the same time, it doesn’t mean we don’t care about the people on our campus,” she says. “It’s reporting with that kind of empathy.”

Looking back on those four days, the lasting impression that has stayed with them was the camaraderie and teamwork.

“Everyone stepped in where needed,” Prasad says.

As a team, they grew “tremendously,” according to Harris.

And in the end, their efforts didn’t go unnoticed. According to Watson, they heard and got feedback from not just people on campus, but readers in the wider Winston-Salem community, including journalists from other papers. It just affirmed that the work is needed, especially now.

“I think the biggest thing I took away from the experience is that student journalism matters, too,” Prasad says. “In my time at Wake Forest, the presence of our newspaper has never felt stronger.”

Read the Old Gold and Black’s coverage of the pro-Palestine protests and encampment here.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

I am not affiliated with WFU but I live near the campus and I read the OGB often. During the protests, the OGB had by far the best coverage. I hope these young journalists go on to have great careers, and I know their journalism teachers and mentors must be very proud of them.