by Brian Clarey

A capacity crowd packed the tiny movie house below Geeksboro for the kickoff feature of its Hayao Miyazaki anime festival, My Neighbor Totoro, a 1988 feature by the esteemed Japanese director and animator.

Miyazaki had been working for two decades prior to the release of Totoro, but this film was part of a burst of creativity for Miyazaki that brought his style and name to the fore of the genre.

For all its cultural cachet, anime is just the word used to describe Japanese cartoons, as opposed to manga, which is what the Japanese call their comic books. And since Totoro’s time, anime has become part of the global mainstream. One of my sons is in an anime club at school.

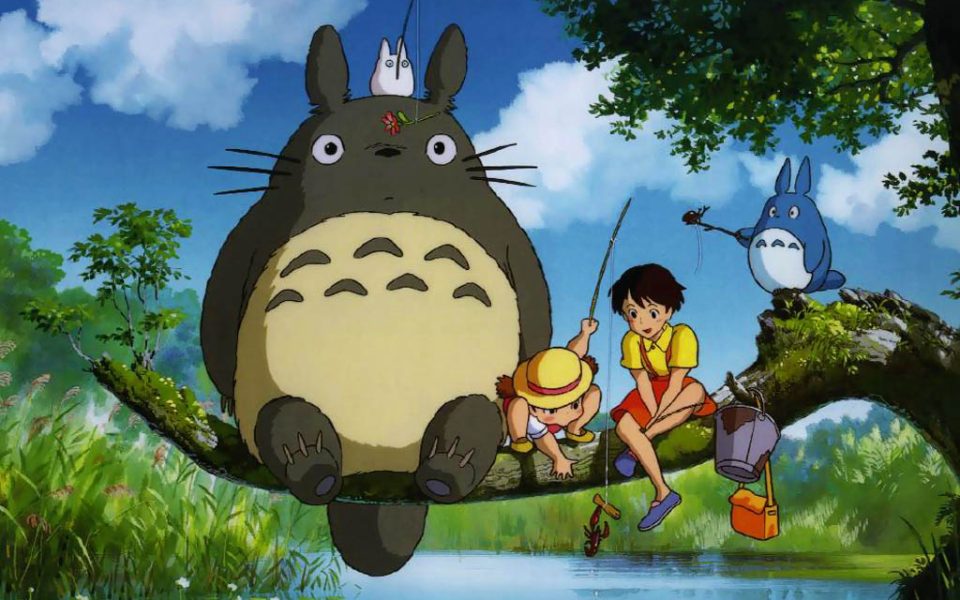

Anime covers a broad spectrum of themes — this weekend’s feature, Howl’s Moving Castle, deals with war and the supernatural. Totoro is one of the more innocent anime films, the story of two young sisters who discover a tribe of fat, bearlike creatures in the woods near their new home.

But through the Japanese school, and particularly Miyazaki’s work, runs similar themes: reverence for nature, a clean and youthful animation style, and the wisdom of children.

Like in many Miyazaki films, there are no good guys or bad guys. The conflict is born of discovery: What are those strange things bouncing through the woods? Towards the end, a missing child adds a necessary bit of tension.

Miyazaki also favors female protagonists, though in Totoro, the mother spends the entire time in the hospital while the two young daughters, wide-eyed and giggling, carry the action. The kids actually act like kids, which is not always the case in anime. And the father, a university professor, is characteristically earnest and clueless.

Because it’s a 25-year-old film, nearly every anime cliché is represented: high-pitched laughter, little girls in tiny clothes, that thing with the eyes. The giant Totoro looks like a Pokemon.

But at times the piece lends itself to good-old American psychedelia. The Cat Bus — yeah, a cat that’s a flying bus — is drawn straight from the acid-drenched representations of Alice in Wonderland. And the anthropomorphized dust motes the children chase through their new house — spirits called susuwatari — look and move a little bit like Woodstock from Peanuts.

Totoro took honors the year it came out, winning the MainichiFilm Award and the Animage Anime Grand Prix prize. And it’s easy to see why. I brought my 11- and 13-year-old sons, who sometimes seem completely jaded by video games and some of the more mature content they’ve digested through various screens throughout the household, and they absolutely loved it, laughing uproariously at the Cat Bus and pretty much everything the giant Totoro did. They’ve been humming the theme song for days.

“I will say: It leaves me with more questions than answers,” my 11-year-old said afterwards. That’s what I mean by “jaded.”

We all agreed that the best laugh of the night went to Joe Scott, proprietor of Geeksboro, who introduced the film with the story of how he first came to know about My Neighbor Totoro.

He was working for Up With People, a multicultural youth music act, and noticed a few of his Japanese students were calling him “Totoro.” Then he saw the film.

“Great,” he said. “It’s a big fat bear.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply