What does it mean to be seen? Strip away a person’s monetary possessions, family history, finances or education — could you define an individual beyond her gender or skin tone and the preconceived notions that are tied with those attributes?

Seven artists deliver their interpretation of what it means to be made visible in the exhibit Do You See Me? The exhibit, on display at the Diggs Gallery on the campus of Winston-Salem State University, includes work from Davion Alston, Jordan Casteel, John Edmonds, Ivan Forde, Aaron Fowler, Zun Lee, Terence Nance, Chris Watts and Lamar Whidbee, who use photography and mixed media to give viewers an intimate look at different marginalized segments of society, particularly African Americans.

Photographer and writer John Edmonds displayed 13 photographs of a black man wearing a black hat and partial facemask in his section “All Eyes on Me.” The most prominent and visible part of the man’s face: his eyes. At times he looks as if he notices something going on behind the viewer, while at others he looks as if he is the one being watched. In one portrait, he appears to be motioning to remove the black mask that covers his mouth. With his hand near his mouth, eyes simultaneously showing fear, one image begs the question whether there is something happening in the foreground making him feel compelled to remove the mask.

In his collection “Food for Thought,” Alston displayed six archival pigment prints of seemingly harmless objects that have now become symbols of cautionary tales for black Americans.

The first two portraits, for example, contain a bag of Skittles. In the first frame, the unopened bag of the candy sits upright and feels unthreatening by itself. In the next one, the bag has been opened. Although void of a human entity, the piece obviously represents Trayvon Martin.

The first two portraits, for example, contain a bag of Skittles. In the first frame, the unopened bag of the candy sits upright and feels unthreatening by itself. In the next one, the bag has been opened. Although void of a human entity, the piece obviously represents Trayvon Martin.

While many of the works contained within the exhibit showed examples of how black Americans are negatively perceived in society or chronicle the tragic events where minorities have been wrongfully targeted, award-winning Canadian photographer Lee used his collection to go in an opposite direction. “Father Figure” positively displays the active role black fathers play in the lives of their children, a contrast to the adverse image perpetuated in society.

In one documentary portrait taken in New York in 2013, Jerrell Wills teaches his son how to brush his teeth, while in another image he is seen hiding behind a door and crying into his hands as his son stays shielded from his moment of vulnerability. Lee’s section also includes pictures of fathers touching the hands of their children through glass and windows as if saying goodbye and a daughter playing with her father’s head as he tries to get her to go to bed.

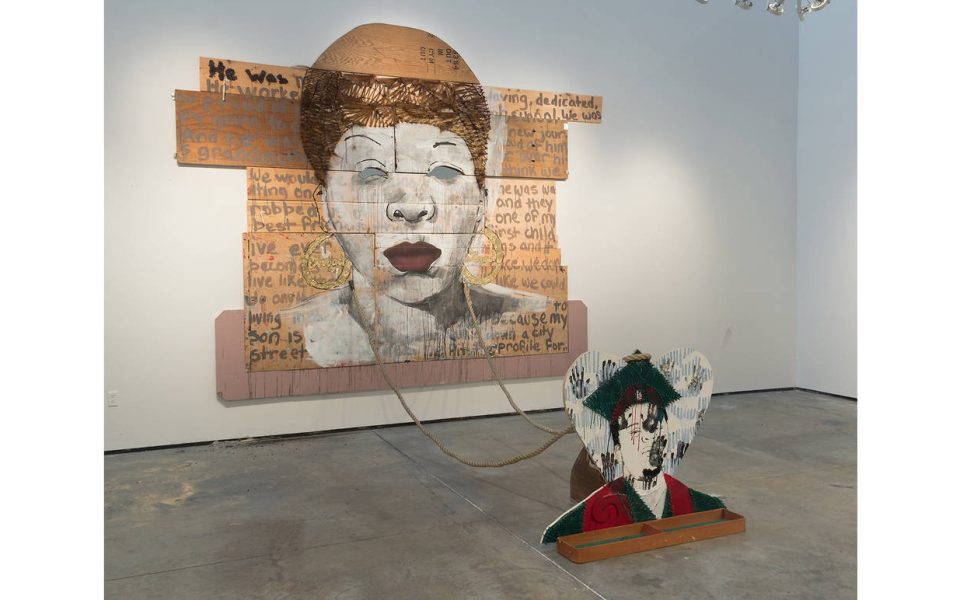

The strong connection of parent and child also comes through in Fowler’s installation about Michael Brown and his mother, Lezley McSpadden. The piece contains words from McSpadden’s eulogy for her son, painted on abandoned plywood. The words “he was” stand out among all the others cast in the paint along with one set of words formed out of dirt and gravel.

Woven within the piece is a portrait of Brown’s mother, her hair created out of hair extensions and construction nails. Fowler made her eyes with pieces of oval mirrors, one with a crack that stretches across the length of it, reflecting the image of anyone who stands in front of the installation. There is a heavy looking rope that stretches out from the wall and connects to another piece of plywood that contains a painted portrait of a younger Brown. The rope used to tie the fixture of Brown to the painted portrait of his mother recalls both an umbilical cord and the history of enslavement.

It’s haunting and somewhat heartbreaking, as are other components of the larger exhibit, which work in concert to illustrate the overlooked depths of black Americans’ humanity amidst an often indifferent and sometimes deadly broader culture. The artists’ messages, while divergent in tone and presentation, compel visitors to wade deeper into the pain and joy contained within the pieces, reflecting the weighty historic-yet-current epoch.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply