Vivian Reed holds the line

by Brian Clarey

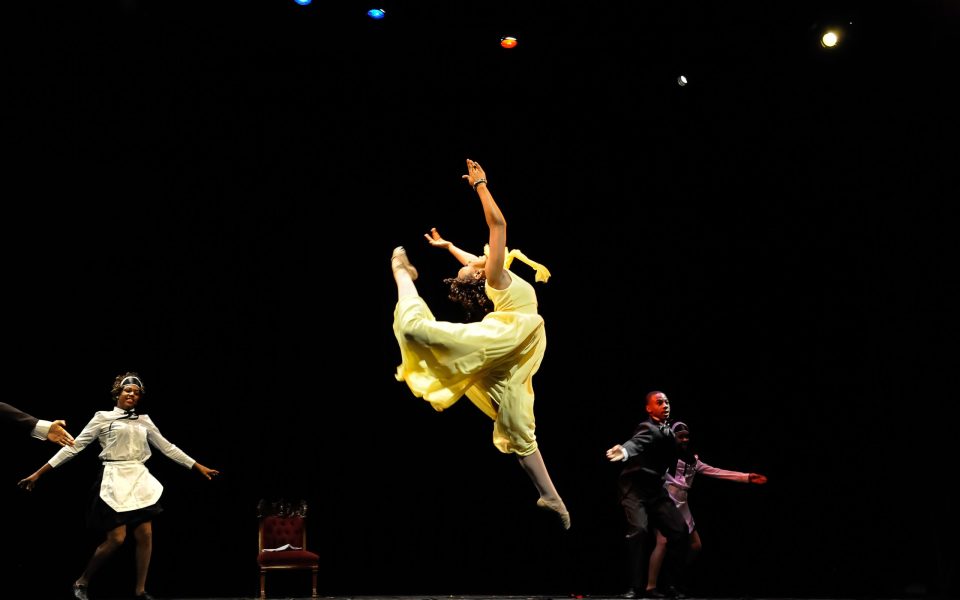

The National Black Theatre Festival devotes much of its schedule to up-and-coming theater and film crews and avant-garde pieces that wouldn’t find a home anywhere else. To balance the schedule, staples like gospel acts, Broadway revues and classic performances run every night.

Vivian Reed manages to cram all of these mainstream categories into just one act.

Elements of her entire career make it into the show: years of classical voice training at Julliard with equal time spent onstage at the Apollo Theatre; another decade of dance; her Broadway debut in Bubbling Brown Sugar, for which a role was created just for her; her Josephine Baker years in France, spent interpreting American classics for European audiences and, eventually, on screen portraying the jazz singer in 1987’s La Rumba.

“My act is very eclectic,” she says. “In ‘Strange Fruit,’ we do a classical composition. Everyone has to be trained classically. Nothing is done like you’ve heard it. ‘Fever’ has a different bassline. Funky. ‘Come Rain or Come Shine’ is funky, as opposed to a jazz standard.

“I talk about it in my show,” she continues. “The joy in any performer comes from taking the time to look at a piece of music, see how you can make it your own without disturbing the integrity of the piece.”

A consummate performer, Reed’s career itself provides much of the material for her stage show.

“I speak off the cuff,” she says. “I basically talk about my beginnings. I don’t do these long-ass monologues — I don’t do none of that. Not every song has a setup. But it’s very… when I say personal, it’s like if you would gather a bunch of your friends and say, ‘Sing a few songs for us.’ That’s what it’s like. It’s like sitting in my living room.”[pullquote]

An Evening with Vivian Reed runs Wednesday through Saturday at the Gaines Ballroom at the Embassy Suites. Buy tickets at nbtf.org.

[/pullquote]

After her voice — discovered in a church choir in Pittsburgh — brought her to Julliard in New York City, she fell in with the crowd at the Apollo. Theater owner Bobby Schiffman became her manager, booking her on nights and weekends while she was studying voice by day.

That, she says, is how she met Bill Cosby, who made his Apollo debut at the time.

“He was just a gentleman,” she says of the now beleaguered actor, who has been accused by several dozen women of sexual assault. “I can only speak on the time I worked with him. I can only speak for myself, and I can’t say that he ever treated me like anything other than a young lady. And I was young, honey. I was one hot little something.”

Her first Tony nomination came from her debut in Bubbling Brown Sugar, largely on the strength of her song-and-dance treatment for “Sweet Georgia Brown” and a big tap number towards the end of the show.

A recording contract brought her through Nashville; movies and television called her to Los Angeles; a stint teaching at the Berklee College of Music gave her a Boston residency.

Over the years she’s crossed paths with Patti LaBelle, Elaine Stritch, Catherine Deneuve, Quincy Jones and Sammy Davis Jr. When she scored a part in the New York production of Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope, she befriended a young Nell Carter, who would soon go on to stardom in Ain’t Misbehavin’ and a starring role in TV’s “Gimme a Break.” Carter died in 2003.

“She did something I should have done,” Reed says now, from her home in New York City. “Universal offered me a [television] contract and I turned them down. I turned down a lot of TV — back then if you did too much TV you couldn’t get into the movies. But [Carter] actually took the deal, and the rest is history.”

The business of show has changed significantly in other ways since she began in the 1970s, as has the artist herself. But she still sees a dearth of opportunity for performers of color, and a strong need for the National Black Theatre Festival.

“You know how many talented African-American artists exist in this world?” she asks. “Some of these wonderful, wonderful, talented people will never see the light of day. Even performers who are extremely established, they don’t have a lot of roles coming to them.

“That’s why I love the festival,” she continues. “It’s a great outlet for a lot of people who would otherwise go unsung. It’s an opportunity for playwrights, for composers and actors to do what they do, and for people to put their shows together and show their talent.

“We need it, honey. And I hope it never goes away.”

Playwright embodies Truth

by Daniel Wirtheim

While Sandra Jones was working at a local television station in 1987, she needed to come up with something for Black History Month. What transpired was a 20-minute segment in which Jones dressed up as the African-American abolitionist Sojourner Truth and performed her most famous speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” It was such a hit that Jones started getting calls to perform at churches, birthday parties and family reunions.

Following the success of the performance, Jones started researching the life of Truth and wrote a play to be performed by one actor.

Jones’ play, Sojourner Truth, A Legacy, tells the story of a Dutch-speaking slave born in the late 18th Century New York, and whose legacy includes fighting for African-American and women’s suffrage rights in Washington, DC.

Mabel Robinson, the artistic director of NC Black Repertory Company based in Winston-Salem, directs Sojourner Truth, A Legacy. Lael Jones, a violinist and Greg Ince, a djembe drummer, will accompany Jones’ performance.

The play tells Truth’s story through multiple characters, all performed by Jones. There’s an auctioneer, a slaveholder, Truth’s mother and Truth herself as a young and old woman. Jones said she researches the intonations and speech patterns of each character, and uses live music as a timing mechanism and to accompany her in song. One of those songs, “Pleading for My People,” was written by Sojourner Truth.

“We were not ‘slaves,” said Jones. “We were ‘enslaved.’ And even when [Truth] was freed, she had obstacles.”

Through her research, Jones came to know her subject as “Mother Truth,” a woman with an incredible capacity for hope in the face of adversity.[pullquote]

Sojurner Truth runs at the Milton Rhodes Center for the Arts on Friday and Saturday at 3 p.m. and 8 p.m.

[/pullquote]

“When you first start reading, you’re going to see her as an orator,” said Jones. “But during my research I got a close-up picture of what it was like to be enslaved, a mother and a woman in love with a man from another farm.”

Truth’s lover died when his master beat him to death for pursuing the illicit romance. Within two years of being freed, Truth went to court to free her son who had been illegally sold to an Alabama slaveholder. She became the first black woman to win such a court case against a white man, Jones said.

Jones believes that Truth’s story has the potential to inspire a younger generation.

“I woke up one morning out of a dream and I was dreaming about how important this is to young children,” said Jones. “Young people now, we’ve got to do better. It’s sad to say that not a lot of things have changed.”

The Bluest Eye delivers literary tragedy

by Chris Nafekh

To address the hardships of self-acceptance that young women everywhere struggle to overcome, particularly black girls, NC Central University is bringing The Bluest Eye to Winston-Salem’s National Black Theatre Festival.

The festival will be the third time NCCU’s drama department has run Lydia Diamond’s adaptation of Toni Morrison’s seminal book The Bluest Eye. The production premiered in April 2014 and was performed at the American College Theatre Festival this past February. The plot is heartbreaking; The Bluest Eye evokes a sorrow that does not fade easily.

The play begins with Pecola Breedlove, played by recent graduate Moriah Williams, arriving at temporary foster care after her unstable alcoholic father burns down their home. In foster care she meets Claudia and Frieda, played by seniors Deja Middleton and Kayln Smith, respectively.

Throughout the play, she is constantly reminded that she is “ugly.” With her self-confidence battered at every turn, young, black Pecola wishes to be white with blue eyes, what society has taught her is beautiful.[pullquote]

The Bluest Eye will be performed on Thursday and Friday night, and in the afternoon and evening on Saturday. All showings will be held at Winston-Salem State University’s Dillard Auditorium in the Anderson Center. For more information, visit nbtf.org

[/pullquote]

“[The Bluest Eye] looks at the prominent challenges of society on a women’s self-esteem in the making of who she is,” said the director, NCCU theater professor Stephanie Asabi Howard. “It focuses on women in general, the idea of beauty, particularly what society presents to us and how we compare ourselves to that. Then of course, looking at it a little deeper as an African-American woman and the different challenges that society may place in her life.”

Howard has made a few forays into African-American literature and history. She wrote and directed God Spoke My Name: Maya Angelou as an original biographical play about the renowned poet. Howard has also directed The Color Purple, a play that shares a common, somber theme with The Bluest Eye.

“The Bluest Eye,” Howard said, “is basically the story of a person who was called names and couldn’t get over it, that took in all the negative and, in a metaphorical way, wasn’t able to spit it back out. It’s probably the saddest play I’ve ever directed. With The Color Purple, you do leave with a sense of empowerment for Celie. There is no sense of empowerment for Pecola.

“As society members, we’re forced to look at Pecola’s mental and spiritual demise because she was not able to take pride in who she was,” Howard continued. “I guess in that way, it is a way to look at the lack of empowerment that would make us responsible for who we are and for children born in society who we could have a negative effect on, particularly for minorities. I try to figure out what is the hope you leave with this play. To the younger people, they leave thinking ‘I don’t have to succumb to society to feel good about myself.’”

Inertia in Levy Lee Simon’s blood

by Eric Ginsburg

Like a train moving at high speed, Levy Lee Simon likely couldn’t slow down if he wanted to. He’s a major component of three plays coming to this year’s festival — as an actor, producer, playwright and director. Inertia, it appears, is in his blood.

“I surely have not come down wearing all those hats in one year, no no,” Simon said from Los Angeles last week. “I don’t think anyone has. It’s an honor, of course, and it’s a challenge.”

But for someone who holds the National Black Theatre Festival “in the highest regard,” and who has made the trek from New York or LA to Winston-Salem numerous times, the three plays he’ll be a part of aren’t necessarily the highlight of his week.

It’s the festival itself.

“To come down and to be a part of something that is so magnificent and is so grand,” he said, trailing off and then adding: “Any time you have thousands of black people coming together, feeling good, looking good… the energy level of it is unmatched anywhere. It’s certainly inspiring at the least and life-changing at the best.”

Simon is looking forward to reconnecting with the festival family, but he’ll hardly have much downtime. His play The Last Revolutionary will make its premiere this week. After the one-hour play, there will be an intermission and the audience will return to witness Dutchman, directed by Simon and written by the legendary Amiri Baraka.

And earlier in the week on Tuesday and Wednesday, the Robey Theatre Company from LA is scheduled to present The Magnificent Dunbar Hotel, which Simon wrote. It recently sold out 29-straight performances in LA, he said.

And the day after he returns home from the National Black Theatre Festival, he’ll hold auditions for a new production.[pullquote]

Catch The Magnificent Dunbar Hotel on Wednesday and The Last Revolutionary along with Dutchman Thursday through Saturday. See nbtf.org for details.

[/pullquote]

Simon received acclaim for his trilogy on the Haitian revolution called For the Love of Freedom. Given that much of his writing deals with political issues and the black experience, it isn’t surprising he considers himself a sociopolitical artist. The Last Revolutionary is no different.

Growing up in Harlem, Simon witnessed some of the black power movement first hand, and he knows several people who were involved in the black liberation movement, in the 1970s as well.

“I’ll never forget the energy of that time, and the images of that time, you know the Afros and the dashikis and the threat of a revolution,” Simon said. “So I created a character who was kind of stuck in those days, even though we’re well past 2000.”

Mac Perkins, the lead character, is still waiting for that revolution, and sees a need to protect Obama. A confrontation with a friend who participated in the historic liberation struggle turns serious, but the play maintains a sense of humor, Simon said.

“In the end it becomes very, very real, and it’s brought up to date,” he said. “Obviously we’re in this new hotbed in political times here. Is [Perkins’] stance archaic or is it not? That becomes the major question that the play raises.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Enjoyed…