One afternoon in 2014, Charity Thomas and her boyfriend, Maurice “Boss” Hagler, found themselves being followed by a strange car as they drove across High Point.

Thomas and Hagler operated Kenzie’s Event Center, a venue on Brentwood Street in High Point named after Thomas’ daughter that functioned as a nightclub while also hosting weddings and children’s birthday parties, and Hagler often helped Thomas at a clothing store she owned. When Thomas and Hagler eventually stopped at the clothing store, the occupants of the car approached them and identified themselves as a criminal defense attorney and private detective. The lawyer was representing Nathan “Goodfoot” Wilson, who was charged in the murder of Gerald Williamson, who was killed at Kenzie’s in the early morning hours of Feb. 28. Thomas had made the 911 call to report the murder and was presumably one of the few reliable witnesses on the scene.

“They were asking if the witnesses that had given information against him were present in the club; we didn’t know,” Thomas recalled. “We didn’t see him do it. When I explained that to them, they could see that me and him wasn’t any help to them. Maurice didn’t have anything to tell. We didn’t see him do it. We didn’t see him with the gun.”

Months later, on a Friday in December, Thomas picked Hagler up after a work shift. They had plans to have dinner together at Golden Corral, and then Thomas would drop him off at his house while she worked a couple hours at the clothing store. Afterwards, the two of them planned to go to Walmart to take care of some Christmas shopping.

As they rode together to the restaurant, Thomas could tell that Hagler was worried about something, but he wouldn’t tell her what it was. He told her it was nothing and turned up the music — Frankie Beverly & Maze — and the couple sang along. At the restaurant, they talked.

“He told me I was his best friend,” Thomas recalled. “We always joked about it — I would tell him, ‘You don’t have any friends.’ It made me smile so much. I laughed, and we held hands and walked out together.”

Just before dropping Maurice off at his house on Wise Avenue, Charity told him: “Have a good day. I love you.” Maurice smiled back at her.

While he waited for Charity to return, Maurice opened his house to five visitors — acquaintances from the neighborhood. Just before 10 p.m., two other men battered down the back door. According to one of the guests, who spoke to Triad City Beat on condition of anonymity, one of the men yelled, “Where’s the money?” before shooting Hagler in the torso. The guest said she picked up someone’s cell phone and called 911, and then observed with disbelief that the other guests were grabbing Hagler’s belongings and fleeing the house. Hagler was pronounced dead after being rushed to the hospital.

Audria McIntyre, Hagler’s mother, said four people who had been at the house before the break-in stole cash out of her son’s pocket after he was shot, along with clothes, baseball cards and a suitcase full of vinyl records.

“I guess he thought he knew them pretty well to invite them over there,” McIntyre said. “They evidently weren’t his friends.”

Much of the information that has come out about Hagler’s murder amounts to little more than rumor.

“It’s absolutely ridiculous that there were five people in the house, not to mention the two people that came in the house, and no one can say what happened,” Thomas said. “Everybody’s story is different. One person upped and moved to Virginia. We asked the police: ‘Do you know where they are?’ They said, ‘We don’t know where they are.’ They said, ‘We went and talked to someone when they were in jail.’ It’s constant BS. It’s unfair to us.”

Thomas doesn’t know who killed her boyfriend, but she’s certain that the people who were with him that night know something that they’re not sharing with the police.

“How can someone come in the house with nothing on their face and no one can tell you nothing? The two guys in the house, they were from the neighborhood that he was trying to help. Me and Maurice took one of the guy’s daughters to church. Two or three days after Maurice died, he up and left. He’s making videos about [the murder].”

Thomas does not connect the crime against her boyfriend to the murder of Gerald Williamson at Kenzie’s Event Center earlier that year.

“Definitely to take what was in the house — money and things that were found in the house,” she said, describing what she said is the most likely motive. “I asked that myself: ‘Lord, I just want to know.’ I can’t even say. I don’t really know. I really would love to know.”

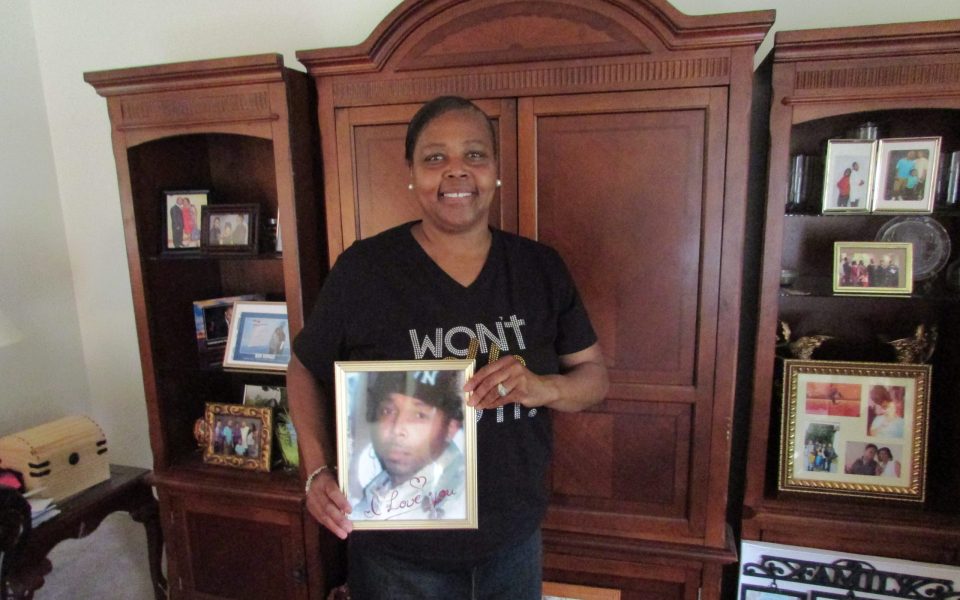

More than two years have passed since Hagler’s death, and Thomas said she still hasn’t gotten used to the fact that he’s gone. He was like a father to McKenzie, who was 8 at the time of his death.

©

“I’m still in mourning,” Thomas said. “I still have my days when I cry out loud. It hasn’t changed. It’s like he’s on a long vacation. My daughter said, ‘It seems like he’s still going to walk in the house.’

“Man, they just don’t know what they took,” Thomas said. “They took someone that was really special.”

McIntyre, his mother, said that she wants the closure that would come from someone being charged in her son’s murder, although a trial would bring up painful feelings.

“I probably won’t understand it, but at least give me clarity,” she said. “Why would you do it? Your life changed, and definitely Boss’ life changed. Who are you? Who are your parents? Who raised you? How can you walk away like you threw something in the trashcan? I’m scared for you because sooner or later the coin will flip. This family keeps praying. We gonna be all right. I can hear Boss saying: ‘We gonna be all right.’”

While expressing hope that those responsible for her son’s death will turn themselves in, McIntyre said, “I have to forgive them for me. If I don’t forgive them, I’m gonna go down a bad road.”

Thomas said that before her boyfriend was killed, she would cry when she saw Gerald Williamson’s daughter at church, and she said she told Hagler she didn’t ever want to have to go through what Williamson’s girlfriend experienced.

If anyone thinks the two murders are connected, Thomas said, “Let it be known that just as much as I want justice for Maurice, I want it for Gerald as well.

“I just pray to God that one day we will get some type of justice,” she said. “I pray for it every day: God help us and give us strength. My heart goes out to Gerald’s family. I pray that we get the justice we deserve.”

CLICK ON THE TAB BELOW TO READ MORE >>>

Compared to its more populous Triad neighbors — Greensboro and Winston-Salem — High Point had until recently maintained an enviable record on violent crime. A 2014 investigation by Triad City Beat found 1.1 homicides per 100,000 people in High Point over a 12-month period, compared to 2.4 in Winston-Salem and 2.8 in Greensboro. The same review found that High Point also compared favorably on its clearance rate, with arrests in 75 percent homicides, compared to only 47.7 percent in Winston-Salem and 59.3 percent in Greensboro.

A city of 111,223, High Point has been shaken by a rash of homicides since the beginning of 2017. The city recorded seven homicides in 2015 and the same number in 2016 — more than twice the figure for 2014. With 2017 not even half over, the count is already at 11. Assuming the trend continues through the end of the year, that puts High Point at a homicide rate of 22.3 per 100,000 people, an astronomical rate when compared with the numbers from just three years ago.

Meanwhile, a growing number of unsolved cases, primarily involving black men in their twenties and early thirties, is straining trust between the police and the black community. Three of the 11 homicides in 2017 remain unsolved, along with three in 2016 and two in 2015, according to Capt. Mike Kirk, the public information officer for the department. And an arrest doesn’t guarantee a conviction: Nathan “Goodfoot” Wilson, the man charged in the murder of Gerald Williamson at Kenzie’s Event Center, walked out of the High Point Jail after 11 months of incarceration when the Guilford County District Attorney was forced to dismiss the case for lack of evidence. The case against Wilson had been built on the word of two informants of questionable credibility, and prosecutors concluded there wasn’t sufficient evidence to support the charge when state lab results showed no DNA match between Wilson and shell casings recovered from the scene.

A handful of family members and intimate partners of black murder victims interviewed for this story alleged treatment by investigators ranging from indifference to intimidation — a charge vigorously denied by department brass. Drug sales as a driver of homicides and other violent crime has also become a point of contention between police and the community. While the criminal records for some victims partially back up the police’s position that violence mainly affects people engaged in the drug trade, the characterization is highly offensive to some family members who find it to be a gross generalization that excuses official complacency.

For many of the mothers and intimate partners of black men killed in the past three years, the recent spate of violence in the first half of this year has reopened old wounds while galvanizing them to come together for mutual support. Led by Tonya Thornton, whose nephew Michael J. Davis was fatally shot in front of his house in the Five Points neighborhood, the women have been meeting roughly twice a month since February in a conference room in the Radisson Hotel in downtown under the banner We Are the Community. A broader cross-section of the community, led by the High Point NAACP, has been holding meetings at a different church in the city once a month to wrestle with the violence, along with other issues of racial inequity.

High Point’s reputation for both proactive policing and race relations — factors bearing on the handling and resolution of the unsolved murders of black men — stands on starkly divergent perceptions.

Local boosters point to High Point Community Against Violence, a nonprofit based in the West End neighborhood that works with the police to reduce violence, including a celebrated call-in program in which violent felons received harsh warnings from law enforcement while a separate panel of community members promises support if they pledge to turn away from criminal activity.

The National Network for Safe Communities at John Jay College states on its website that High Point “has seen major reductions in crime over 20 years using the [project’s] strategies and conducting call-ins.

“It was the initial pilot site for the Drug Market Intervention and has helped to develop innovations such as racial reconciliation and custom notifications,” the website says.

The website for the program credits High Point Community Against Violence with providing “a template for community partnership in violence reduction efforts across the country” while noting that High Point was also the pilot site for an “Intimate Partner Violence Intervention” program in collaboration with the US Justice Department’s Office on Violence Against Women.

Meanwhile, former Chief Marty Sumner, who retired in February 2016, defended officers who walked out on a training about institutional racism hosted by Guilford County Schools in early 2015. Subsequently, complaints from conservative city council members about a “Black and Blue” forum to promote dialogue between the police and the black community organized by the High Point Human Relations Commission ultimately led to the firing of Human Relations Director Al Heggins, who has a federal lawsuit for racial discrimination pending against the city.

Pastor Brad Lilley, an officer with the High Point NAACP, has characterized the city’s dismissal of Heggins and the suspension of her program to promote police-community dialogue as a squandered opportunity. Based on the fraught relationship between Lilley and department brass — notably Sumner’s successor, Kenneth Shultz — the police have largely shunned the NAACP-sponsored community meetings, further alienating black residents and eroding trust in the department.

CLICK ON THE TAB BELOW TO READ MORE >>>

“I know he wasn’t a perfect son; he was my son,” Audria McIntyre said about Maurice Hagler, who was murdered in December 2014. “I know he got caught with marijuana.”

Hagler faced felony marijuana charges at the time of his death. An affidavit attached to a search warrant in the case indicates that TA Weavil, an investigator in the Guilford County Sheriff’s Office’s vice-narcotics unit, had met with an informant who indicated that Hagler was distributing “large amounts of marijuana” from the house. The affidavit warned, “This informant fears physical reprisal should the informant’s identity become known.”

Similarly, Jauhan Bethea, who was fatally shot in his house on Burton Avenue in September 2015, carried a 2007 conviction for trafficking MDMA, commonly known as molly, in 2007 and 1999 conviction for cocaine possession.

©

Bethea, who was 34 at the time of his death, was quiet and reserved, the type of person who mainly kept to himself, said his mother, Mary Bethea. His father, Melvin Dowe, said Jauhan told him it was hard to find a job because he had a felony on his record.

Dowe said Bethea’s girlfriend and the children had just left for a funeral 30 minutes before someone broke into the house through a window and shot him.

“I know it was someone who knew him real good,” Dowe said. “He didn’t have a lot of friends. His girlfriend had friends over. I feel like it was one of her girlfriends who set him up.”

Mary Bethea added, “Somebody knows something. If it was their child, they would want someone to talk, too.”

Jauhan Bethea had four children. The youngest, Jauhan Jr., was 16 months old at the time of his death.

Now 3, Jauhan Jr. occasionally throws screaming fits because he misses his father, his grandmother said.

“He’s hollering: ‘Dad, dad! Where you at?’”

Dowe said Jauhan had given him a pressure washer for Father’s Day, and they planned to start a side business together to earn extra money.

“There’s stuff we had been planning to do,” Dowe said as his wife wept. “I don’t bring up stuff like that because it’s hard for her — little stuff we had been planning to do. That Father’s Day was one of the best Father’s Days I had.”

Before Jauhan died, Dowe told him about his plans to buy a storage unit to put in the backyard.

“I said, ‘Jauhan, I finally decided to get the storage building,’” Dowe recalled. “They were building it, and they delivered it the day before his funeral. I think about him every time I step into the storage shed.”

Dowe said he’d like to know some details about Jauhan’s murder like whether there was evidence of a struggle and whether the house had been ransacked.

“We don’t know anything,” Dowe said. “It seems like [the police] avoid us.

©

“I went there [to the police department], and they wouldn’t even send someone to talk to us,” he added. “I’ve only been a law-abiding citizen. When this happened I got a different perspective on law officers.”

Assistant Chief Larry Casterline dismissed Dowe’s account as “ludicrous,” adding that he could come to police headquarters and file a complaint with the professional standards division if he wished.

“If that detective was there, and they didn’t have someone at their desk, they would come out,” Casterline said. “You’re not going to ignore someone who calls you a ‘racist.’ This is 2018 [sic]. We are about customer service.”

The High Point Police Department now considers the cases of Gerald Williamson, Maurice Hagler and Jauhan Bethea to be “cold,” said Lt. Rick Johnson, who supervises the violent crimes unit.

“Obviously, the overwhelming percentage of violent crime is drug-related, or related to mental health or alcohol,” Casterline said. “It’s typically not innocent bystanders that are the victims. When you read about drive-by shootings, 95 percent is two groups going back and forth. You’ll have the Bloods and Crips with drug gangs competing for turf. They’re robbing drug dealers or places that gambling is going on. They know there’s money there. They know they’re not going to call the police because the victims don’t want the police involved.”

Many, though not all, of the family members and intimate partners find Casterline’s characterization to be infuriating.

©

Michael J. Davis was fatally shot in his front yard in the Five Points neighborhood in October 2016. Although Davis carried a conviction for felony robbery with a dangerous weapon when he was in his early twenties, his record does not include any drug charges.

“He was not an innocent person; just a regular person,” said Davis’ aunt, Tonya Thornton. “He was 34 years old with four kids; great father. He grew a garden. He built the inside of his house with his own hands. Whenever people heard that he got killed, it was, ‘Who? Mike D?’ When he had his first kid he got in trouble. Was it right? No. He owned his home. He wasn’t a drug dealer. He did smoke weed. He worked at Family Dollar full time.”

Thornton said when she and Davis’ mother call the police department, “no one picks up and no one calls back.”

The command staff at the police department is familiar with the charge, and Casterline said the family members leveling it are just upset because the detectives tell them they have no new information.

“Every man and woman who wears the uniform, most are married,” Casterline said. “They have moms, dads, uncles and cousins, and all of them at one time have experienced loss, especially the detectives who are older. If you want your case solved and you want something done, and a detective calls and says, ‘We have no other information,’ frequently they’re not happy with that. But most of [the detectives] will call them back.”

Rosalind Hoover (see related story) — whose fiancé, Donte Gilmore, was fatally stabbed at his home on Franklin Avenue on Feb. 1, said the police have attempted to intimidate her because of her outspokenness about their handling of the case.

“I have even been told that I could not get anything on Donte’s case if I keep speaking out on Facebook and being around Tonya [Thornton],” Hoover said.

“I doubt that highly,” Casterline said when told of Hoover’s complaint. He added that, if sustained, the conduct described by Hoover would amount to a departmental violation for rudeness as opposed to intimidation, and that she should file a complaint with the professional standards division if she feels she has been mistreated.

The fact that Chief Shultz has repeatedly declined to attend or send a representative to monthly meetings of the High Point NAACP reinforces a sense among some family members that the department is indifferent towards the deaths of their loved ones.

“It’s important for meetings to be productive,” Casterline said. “If I know you can’t stand me or you’re not going to be honest with me or it’s not going to be productive… at some point we’re gonna move on.”

Pastor Brad Lilley, who serves as the community coordinator for the High Point NAACP, said Chief Shultz reluctantly attended the first community meeting in March, after Lilley met with the chief and City Manager Greg Demko.

“They were very apprehensive about coming to this meeting,” Lilley said. “As the city manager put it: Was I trying to make them look bad? As soon as I walked into the room, they began to question me. Chief Shultz asked: Was I trying to set them up? They had in mind that I had some kind of hidden agenda. This community meeting was the best thing that could happen to the community. I thought if we stand shoulder to shoulder that those who perpetuate these killings would see that the community is standing united with the police department to stop the violence. That has always been the agenda — to stop the violence.”

Shultz said he would not discuss anything personal between him and Pastor Lilley, but he said he meets with a representative of the High Point NAACP once a week, much as he does with representatives of the Latino community. After he attended the March NAACP meeting, Shultz said he decided it didn’t make sense to have police there because he doesn’t want to discuss personnel issues or specific cases in public. He also said when mothers claim that the police don’t talk to them, it doesn’t do any good for officers to publicly contradict them.

Tonya Thornton — whose nephew, Michael J. Davis, was murdered in 2016 — contends that the police make a broad-brush characterization that black victims of violence are involved in drug dealing as a way to excuse their lack of progress.

“Where black people is getting shot and murdered, they’re treated as suspects instead of victims,” she said.

“We’re asking the police chief: Why aren’t you protecting us? 27260 and 27262 are the ZIP codes you’re policing, but you’re protecting 27265. You’re setting up roadblocks in our neighborhoods. I think it’s their preference. If I’m wrong I don’t think they’re showing me any different.”

That’s not true, Casterline said.

“Our job is to get violent people off the streets,” Casterline said. “Every time a gun is fired, that bullet has to go somewhere. And if it misses its intended target, where’s it going? To me it’s kind of sad that someone would think that, especially the way officers risk their lives every day and put in the time to solve these crimes. The idea that we don’t make the same effort just because of someone’s skin color is outrageous.”

During two separate interviews, Casterline repeatedly emphasized that the police are reluctant to share details with family members for a variety of reasons, including that they might share the information and compromise the investigation or in some cases the family members might themselves be under suspicion. But when challenged on whether his characterization of violent crime as being monolithically driven by the drug trade, Casterline volunteered that investigators have heard “street talk” that Michael J. Davis had “ripped off someone of a large amount of marijuana.” He added that the department was planning to release the information in the hopes that someone in the community would come forward with information that would help police make an arrest.

“I don’t appreciate that they would share it publicly before they shared it with the family,” Tonya Thornton, Davis’ aunt, said. “They don’t talk to us.”

Thornton expressly gave her blessing for Triad City Beat to publish the information, even at the risk that it might defame her nephew, because she believes it’s important for people to know how the police are treating the case.

“It’s always drugs — that’s horrible,” she said. “If your white neighbor got shot, they would not say it was drug-related. They would look for other reasons. That pisses me off.”

Lt. Johnson, who supervises the violent crimes unit, said the department currently considers the investigations into the Davis and Gilmore homicides to be “active, heading towards cold.”

Audria McIntyre, the mother of Maurice Hagler, said she used to call the detective every couple days, but now she figures he’ll call her if he has any new information. She trusts that he’s still pursuing leads even though her son’s homicide is now considered a “cold case.”

“A lot of people are doing a lot of talking, but they’re not going to the police,” McIntyre said. “It’s all rumors. If it was your brother, if it was your nephew, if it was your uncle, you would want that closure. There’s no honor among thieves. They’re going to turn on you. I don’t want another mother to wake up and have a hole in her heart. No mother should bury a child, because it’s a hurting thing.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply