As the temperature climbs in the popcorn machine stationed in the far corner of a High Point YMCA’s massive gymnasium, the moisture in the kernels’ endosperm steams until bursting violently through the hulls — one of the oldest stories: tension, release, transformation.

Basketball nets frame a projection screen propped before the two dozen or so attendees who’ve scattered themselves within a patch of metal folding chairs to view Wilmington on Fire on the evening of May 17. The feature-length documentary examines the seldom-acknowledged, bloody coup d’état white supremacist Democrats carried out in the booming port city of Wilmington on Nov. 10, 1898, a massacre that rendered roughly one-half of the city’s African-American population dead or permanently exiled.

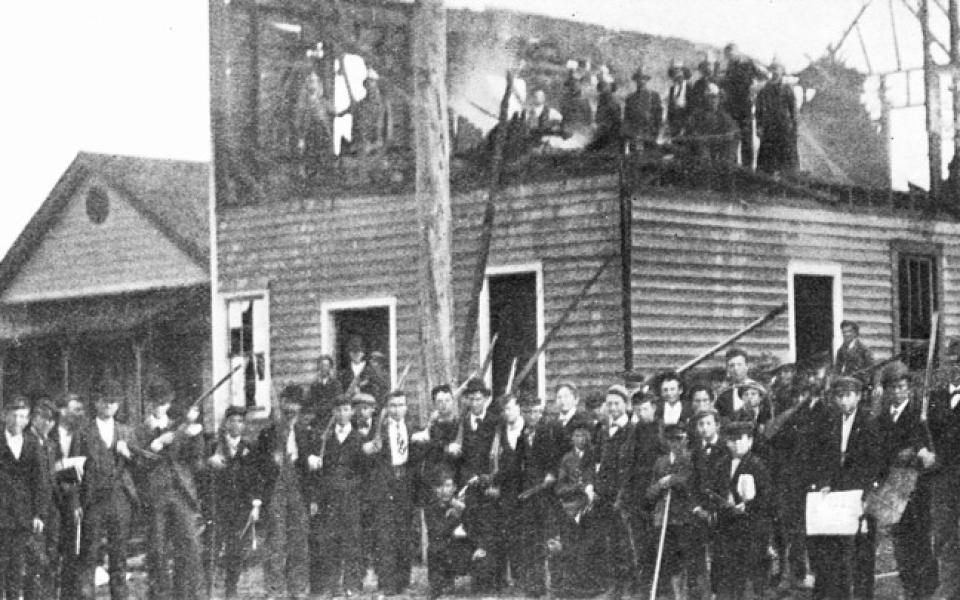

Kent Chatfield, an independent researcher, rifles through mountains of court documents, letters, ledgers and portraits uncovered in dusty government basements throughout the film. He presents a copy of a pamphlet printed by the North Carolina Democratic Party in 1897, which defined the organization of the new White Government Union body and explicitly stated that the aim of the secret political society would be to install a white-supremacist government in North Carolina, beginning in Wilmington. More secretive and organized than the Ku Klux Klan, the group sought to first disrupt the Fusion Party coalition between white populists, mostly farmers, and Republicans, mostly newly freed African Americans. They functioned as an officer class to the Red Shirts, the de facto paramilitary arm to the Democratic Party, which differed from the Klan in that they sported bright red shirts and did not cover their faces or wait for the cover of night before committing their crimes. Chatfield, who grew up white in Wilmington, recalls overhearing men boast of their forefathers’ execution of the only successful coup in US history, of the women and children who hid in the swamps for weeks, of the countless black bodies that floated downstream.

Alexander Manly, publisher of the Daily Record, the only black-owned daily newspaper in the country, grew too familiar with their intimidation tactics. White supremacists cast him as a central character in their 1898 propaganda campaign after he wrote an editorial denouncing the untruth of black men’s propensity to rape white women, a false narrative designed to stoke the ire of white men who might otherwise be sympathetic to African Americans. The Star News, then the de facto paper of Wilmington’s Democratic party, and the News & Observer gladly assisted their cause in the lead-up to the coup, publishing grotesque racial cartoons and plain lies about the city’s thriving African-American community.

According to LaRae Umfleet, who researched and wrote the definitive study examining the riot and its impact as a watershed moment in post-Reconstruction North Carolina politics, Wilmington had been considered a mecca for African Americans at a time when the political process was more fairly representative of them than at most other times in US history; they held roles in the management of the city and county, seats on the board of alderman, in the state legislature and in the US House of Representatives. Wilmington was also the largest and most prosperous city in North Carolina, largely due to its status as a critical, deep-water port. Umfleet explains in the film that African Americans at every economic rung of society experienced relative prosperity. Black shrimpers and fishers continued to pass down trade expertise in the Cape Fear River region; black literacy rates soared; African Americans owned an astonishing number of businesses on main streets, including restaurants; served as police and firemen; practiced medicine and law.

After the coup, only three of 18 black-owned businesses remained. Once black magistrates “resigned,” racist Democrats also ruled the courts and when the state and federal government opted not to intervene, the newly empowered foreclosed on the homes of the dead, refinanced bad loans, inflated stock, lined their bloody pockets and waited with shotguns at the polls.

Wilmington on Fire draws a clear connection between the political and social disenfranchisement and the scope of the generational wealth plundered from members of Wilmington’s half-destroyed black community. Late in the film, Faye Chaplin, the great-granddaughter of Thomas C. Miller, a real estate developer in the city at the time of the coup, cries as she reads aloud a letter he penned detailing the impossibility of starting anew with no wealth — Miller was one of the few “elite” African Americans who the mob forcibly banished by way of a train headed north of the state line. She motions toward the window in her home through which she witnesses the construction of apartment buildings gentrifying the property her kin owned only a few generations ago.

Phyllis Bridges, an award-winning historian and documentary filmmaker with expertise in High Point’s civil rights history, leads an informal discussion after the screening. Some older men seemed to know what they wanted to say over the voices of others before arriving, though, going on about black Israelites and rap culture as cancer. Bridges redirects, comparing the fate of Wilmington’s all-black Brooklyn neighborhood to High Point’s Washington Street community, and an elder gentleman offers some local history: “We had a total of 27 black-owned businesses on Fairview Street in one block, then you had Kivett Drive which basically was a black economic corridor in the city. What they did with the highway was they displaced all those black-owned businesses and did not offer any funds for relocation. Then you had Washington Street, a total of over 150 black-owned businesses that disappeared because of ‘urban renewal.’”

Violence comes in many forms.

A man, white, describes coming into racial consciousness when he learned the history of white terror the next county over from his childhood home in Georgia. He’s ready to speak up more often now, he says. “Now all those coals kept under the surface have been raked up, but the thing is: that fire has been smoldering under the surface this whole time.”

And so, a black woman poses the question: “One of the things that haunts me about this film is the younger man [Umar Johnson] who was talking about the propaganda campaign that preceded the attack on Wilmington and how he thinks it’s worse today,” she says. “I wonder what you all think he’s talking about.”

A man who fits squarely in Fox News’ top demographic contributes proudly, with a holler: “It’s called Fox News!” before other Boomers abruptly shift to lamenting the fall of heterosexual households and other moral failings of young people, none of whom chose to join tonight.

Perhaps it is fair enough that most folks did not assemble in this auditorium on a balmy, full-mooned evening to discuss disturbing parallels to today’s alarms, let alone organize against the ongoing effort for one-party control of the Old North State, as premeditated and resolute as ever. Perhaps, it is critical, and an adequate end in itself, to create spaces for letting off steam, but questions linger: Who might you burn? How will these stoked coals transform us?

Find out more about the film here.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply