It doesn’t look like it was supposed to.

While the structure and the shape is the same, the ghost house at the corner of Waughtown and Main in Winston-Salem isn’t lit up the way it was intended.

Still, the organizers and artists behind “Lines,” the Winston-Salem Light Project’s most recent installation, say it accomplishes the same goal.

“People talk about gentrification all the time,” says Kim Smith, a senior lighting student at UNC School of the Arts and one of the four students who completed the project. “It’s just become a thing now. You know, gentrification, it’s what happens…. But I think it’s starting that conversation, getting people to really start to think about it… and it’s not gonna stop happening, but what can we do to help these people who are displaced?”

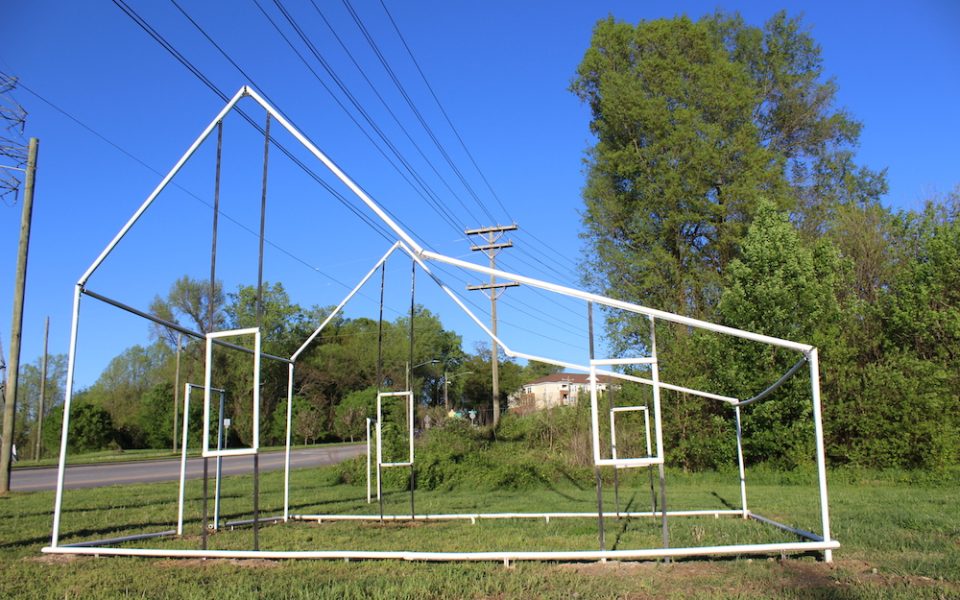

Bright white lines of PEX pipe, stronger than PVC, form the outline of a small, two-story house that would have been typical in 1920s Winston-Salem. A doorframe indicates the sole entrance to the home, while four floating windows materialize out of thin air, held up only by strips of metal beams that connect to the top and bottom frames of the structure. A lone door sits behind the fully constructed house, while three partially formed homes, also made of pipe, fill the rest of the grassy area where the project has been installed.

The installation, which went up on April 12, is the 11th iteration of the Winston-Salem Light Project, which partners with UNCSA students each year to create illuminated public works of art. This year, Smith and her classmates settled on the idea of creating these house frames to give complex concepts like gentrification, displacement and urban renewal a face.

The idea came to light when one of the students began delving into the history of redlining in the city. The systemic denial of access to things like loans, most often targeted at black communities, got its start after the passage of the National Housing Act of 1934, which established the Federal Housing Administration.

“It determined who got loans and who could move to certain areas in the town,” Smith says. “People were shuttled into poor or rich areas based on red lines. The name came from that.”

She also points out the history of how major highways often cut through whole neighborhoods, displacing many of the residents, creating more segregated areas of the city.

The project is meant to illuminate how certain neighborhoods and communities were disenfranchised by racist housing practices and urban renewal.

“We’re using Winston-Salem as the example of that, but it happens everywhere,” says Norman Coates, the director of the project and director of the lighting department at UNC School of the Arts. “You can expand the idea of lines so broadly… the construction lines or the redlining that has divided communities. We look at lines of connection. How do the bridges connect us back and forth? How do we build lines and barriers?”

The installation sits on a piece of property owned by the school, close to Happy Hill, the city’s oldest African American neighborhood. The area where the piece exists used to be a working-poor neighborhood, according to Smith. Now, the plot of land sits at the corner of a busy intersection where joggers cross a nearby bridge and others file in and out of a YWCA across the street. The completed house, which measures 19-by-26 feet, is based off of small, shotgun-style homes that existed here in the early part of the 20th Century while the deconstructed homes and single doorframes are meant to show the breakdown and erasure of residences over the years.

“It’s like, ‘Oh wow, a house used to be here,’” says Smith.

The project, which will be up at least through April 25, took over a year to complete. And along the way, the students say they experienced setback after setback. First, they had a difficult time finding the right materials to create their sculpture. Then they had to change sites because of the timeframe. And finally, when it came to lighting the actual piece, they found that there was no access to electricity to light the tubes, like originally planned, at the final location.

“It was every day that we would move forward came with a laundry list of things to overcome, the things that you almost can’t anticipate,” says Brendan Warner, another senior lighting student who worked on the project.

“I think it would be similar to waterboarding perhaps,” Coates jokes.

So, when visitors witness the sculpture now, it won’t be lit up, but they hope it conveys the same message says Warner.

“What it does is it asks the question, it inspires you to think about what it is and why it is the way it is,” he says. “As long as it’s rooted in what you’re trying to say, it will still say what you’re trying to say.”

“Lines” can be viewed at the intersection of South Main and Waughtown streets in Winston-Salem. Find out more about the project at the Winston-Salem Light Project website.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply