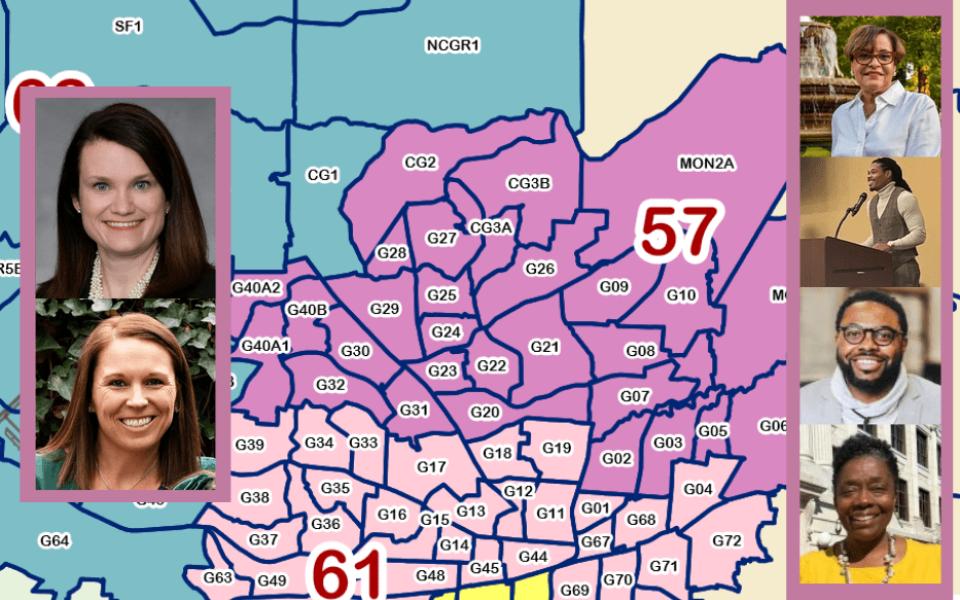

Featured photo: Rep. Ashton Clemmons, Tracy Clark, Linda Wilson, Irving Allen, Blake E. Odum and Lisa McMillan on a map showing House District 57.

When a NC State House seat became vacant earlier this month, Black politicians and candidates jumped at the opportunity for the district to be represented by a person of color for the first time in the district’s history. But in a swift set of events, another white candidate was elected to the seat, dashing their hopes of a change in representation. Now, those involved are filing a complaint at the state level alleging errors and possible collusion in the process.

Note for readers: Throughout this piece there are some paragraphs with arrows (▶) that allow readers to read context. Click the arrow (▶) to read more info.

Last year, when state lawmakers redrew North Carolina’s federal and state maps, those who opposed them pointed out that they were unfair to Democrats and Black voters, prompting a lawsuit by the state’s NAACP.

But in House District 57, situated in Guilford County, the redrawing of the maps placed the district squarely in the central part of the county, incorporating northern Greensboro.

The new map, which will be in play for the November election, makes the district majority-minority for the first time.

Currently, the map for House District 57 includes northern parts of Greensboro and Summerfield and is 57.8 percent white, 26.9 percent Black, 7 percent Hispanic and 7 percent Asian, according to data analyzed by the Dave’s Redistricting App. As it stands, the district leans Democrat by about 15 percentage points. But with the new map, which will be used in the fall election, the district no longer cuts north into Summerfield, and instead, stays in central Guilford County, mostly in the northern parts of Greensboro.

“We’ve never had a person of color [as a] representative in that district,” said Byron Gladden, the head of Guilford County’s African-American Caucus.

Since House District 57 has been part of Guilford County, it has been held by a white representative. From 1985-2003, the district was situated partially in Mecklenburg County and was held by white Republicans. In 2003, when the district was redrawn to include Guilford County, Republican Joanne Bowie lost the seat to Democrat Pricey Harrison who was the representative until 2019. That was the year that Rep. Ashton Clemmons took the seat; she has won every race by 20-30 percentage points against her Republican opponents in the last three elections.

So when Rep. Ashton Clemmons, a white Democrat who has represented House District 57 for three terms, announced her plans to resign from the seat in July, the local Black political machine started to make moves.

“We have a long way to go in this community in terms of representation from all levels,” said Linda Wilson, about local Black political representation. “I think when we look at it and analyze it, we need to make sure that representation is fair and equitable across the line.”

Wilson was one of eight candidates — four of them Black — who vied for Clemmons’s seat last month.

But now, more than a month later, all of the Black candidates who ran for Clemmons’s seat have signed onto an official grievance that was filed to the state Democratic Party earlier this month. They, along with five other individuals, allege that the process by which Clemmons’s successor — Tracy Clark, another white woman — was chosen for the seat was a confusing, mishandled and needlessly hurried process that negatively and disproportionately affected the Black candidates involved.

The allegations include a change in the process of how votes were counted as well as an issue of timing to fill the seat. In one interview, a political expert called the way in which the vacancy was filled “unusual,” based on the fact that the elections took place before Clemmons had actually turned in her official resignation.

Additionally, in conversations with TCB, complainants alluded to the appearance that Clark was the favored candidate and had unfair advantages over other individuals running in the races.

“I think it was totally unfair,” said Skip Alston, the chair of the Guilford County Board of Commissioners and a complainant on the grievance. “One-hundred percent unfair without any doubt in my mind at all. The whole process was unfair from the start.”

On Aug. 8, nine complainants — candidates Irving Allen, Lisa McMillan, Wilson, Odum, along with Alston, Gladden, Elizabeth Paulsen, Frankie Jones and Deena Hayes Greene — filed a grievance to the NC Democratic Party’s Council of Review.

The council, which acts as the party’s body that hears and deliberates on disputes, will hold a virtual hearing on Aug. 25 to determine whether the grievance has merit and issue any action. The bulk of the complaint is directed at Guilford County Democratic Party Chair Kathy Kirkpatrick, who declined mediation.

Now, members of the local party are embroiled in an accelerated grievance process that aims to unseat Clark and redo the elections before ballots get printed next month.

And no matter the outcome, the question of whether the party can come together and unify behind a single candidate come November remains to be answered.

A weighty issue

When an elected official resigns from their seat, or dies, before their term is over, the relevant political party is tasked with holding internal elections to replace the candidate.

In the instance of Rep. Clemmons, who announced on July 15 via X that she was planning on resigning, that left the choice to the Guilford County Democratic Party. And since Clemmons was up for reelection this fall, that meant that two elections would need to be held: one to fill the seat immediately and one to replace Clemmons on the ballot for November.

The way the party does this, as explained by Guilford County Chair Kirkpatrick, is that precinct officials cast their votes, not regular voters. According to state party rules, precincts are made up of at least five registered Democrats who organize and choose a chair and vice chair at the start of every year. While precincts can technically organize any time during the year, in order to be eligible to vote to replace Clemmons, precincts had to have been organized before August.

Here’s where things start to get confusing.

In past instances where there have been vacancies — for example, when Skip Alston replaced Ray Trapp on Guilford County Commission in 2017 — precinct chairs and vice chairs were given a certain number of votes based on the population of their precincts. This method of voting — also known as weighted voting — meant that the more people in the precinct, the higher the number of votes the officials got.

For the Black candidates, this was an important distinction because many of the predominantly Black precincts had higher numbers of registered voters. That meant they would have had more votes than some other precincts.

Initially, the vote to replace Clemmons was set to be a weighted one.

In an initial email to candidates on July 24, Kirkpatrick stated that the votes would be weighted, and in this instance, each precinct would get 1 vote per 100 votes cast by Democrats in that precinct for the Democratic governor in the last election. That ruling was based on the state Democratic party’s plan of organization, or the party’s official rule book.

This method gives precincts with larger populations of Democratic voters more weight to their vote. For instance, officials for precinct G26 in Browns Summit would have gotten 20 total votes compared to precinct SF2 in Summerfield, which would have gotten 6.

But two days later, the rules were changed to a different process that the complainants allege “gutted Black precincts” and took away their voting power.

According to David Parker, a parliamentarian who advised Kirkpatrick on the change, the issue comes down to how the state party’s rules, along with state laws, are interpreted.

“We started off in the wrong place,” Parker told TCB. “But sometimes your initial reading is incorrect, and it was a nonlawyer from another county that pointed out that we were in the wrong section.”

That nonlawyer was Catherine Magid, a Democrat in Guilford County, who reached out to Kirkpatrick days before the election was set to take place to tell her that the votes should be unweighted instead.

In that case, instead of each precinct getting a certain number of votes based on population, they would get two votes — one for the precinct chair and vice chair each.

In this alternative reading — which is noted in Section 3.12 of the party’s plan — Kirkpatrick noted that because House District 57 was contained in Guilford County, but did not make up the entirety of the county, that the correct way to count the votes would be unweighted.

Kirkpatrick noted in a later interview that Magid was supporting Clark.

“That meant that three precincts that are Black just got gutted,” Gladden told TCB.

In the end, Clark won both of the votes, pulling ahead of Wilson by eight votes in each election after the first rounds ended in close runoffs.

“I believe that the outcome would have been different,” Wilson told TCB about the elections. “There were more votes that could have been counted.”

Another part of the grievance alleges that the party’s official reading of the rules was mistaken and that the vote should have been weighted based on the population of the precincts. In this weighted vote, the two precinct officials — the chair and the vice chair — would get 1 vote per 300 people in their precinct.

In an interview, Kirkpatrick stated that she and others ran the numbers as both unweighted and weighted and found that Clark would have won in either case. Clark declined to send TCB a copy of the weighted vote calculations, stating that “they are not official numbers and subject to release.”

And while Kirkpatrick, Parker, Magid and John Wallace, the NC Democratic Party’s lawyer, collectively came to the conclusion that the votes should be unweighted, the complainants argue that they were never given clear reasons for the change in a timely manner before the elections. This prompted the Guilford County African American Caucus and candidate Odum to file requests on Aug. 2 to postpone the election set to take place the next day. Kirkpatrick denied both requests and the elections took place as scheduled.

In an interview with TCB, Kirkpatrick argued that she personally believed that the votes should have been weighted. But after consulting with others, she said she “acquiesced” and changed the process to an unweighted vote.

“I was not in agreement that it needed to be unweighted,” she told TCB.

But Gladden said he doesn’t buy Kirkpatrick’s argument.

“I struggle with Kathy’s response because there is nothing in writing that says she was ordered to do it that way,” Gladden said.

Allen said that as a candidate who was running to fill a vacancy for the first time, the antiquated and confusing nature of the process made it difficult for him to campaign, and to understand his role.

“I don’t know what would have happened with that extra time, but I think we would have been able to get more clarity on the proper interpretation,” he told TCB on Aug. 9.

And therein lies a core heart of the grievance: That many of the candidates involved were confused about the process and that they should have been granted extra time to make sure everyone was on the same page.

Time, of the essence

In addition to the allegations of incorrect process when it came to casting the votes, the grievance also questions the timeline in which events took place, starting with Clemmons’s announcement of resignation on July 15.

When Clemmons announced her plans to resign via X she did so without naming her last day in office; in her statement, Clemmons writes that “she will be resigning.”

The following day, Clemmons is quoted in an Associated Press article that she will wait until her successor is chosen before resigning. On Aug. 3, elections were held to replace Clemmons, who didn’t officially resign from her seat until two days later, on Aug. 5.

That, the grievance states, poses a technical issue of vacancy.

“They went through this process before a vacancy was created,” Alston told TCB.

Those who have signed on to the grievance state that this sets a dangerous precedent wherein a candidate could threaten to resign, wait to see who acts to take their seat, and then retract their resignation if they disagree with the person selected as their successor.

“So then the question is, what if the wrong person that they didn’t want gets chosen to take their seat?” Gladden asked. “They could technically, under the plan of organization… nothing says a person can’t rescind their resignation.”

When asked why the election took place before Clemmons’s official resignation, Kirkpatrick stated that the rules don’t preclude them from holding an election and “having someone ready to go once the vacancy occurs.”

“Nobody told me otherwise on that,” she said.

Again, like with the issue of weighted versus unweighted votes, this issue of timing is unclear in state statutes and the party’s plan of organization; that can lead to confusion and inconsistent reading of the rules.

“My read is that the governor has a timeline, but that the executive committee does not appear to,” Chris Cooper, a political science professor at Western Carolina University explained. “But [the law] is obviously written as if a vacancy is occurring. This is unusual, odd, surprising, all of that, but I don’t know if it is illegal.”

The executive committee is the governing body that handles political business for the party at the county level.

“My read is that it’s unclear,” Cooper said.

This makes taking action like filling vacancies a much murkier process than one might expect.

“This stuff is so much fuzzier than people act like,” Cooper said.

In terms of a hard deadline, there is one countdown that determines how quickly a candidate will need to be chosen. And that’s the preparation of the ballots for the November election.

According to the NC Board of Elections website, county boards of elections will start mailing absentee ballots for the election on Sept. 6. That means a candidate to replace Clemmons on the ballot will need to be determined before then.

When asked about a timeline, Guilford County Board of Elections Chair Charlie Colicutt didn’t note a hard deadline, but instead stated that the law says that names need to be provided “before ballots are printed.”

In an email on Aug. 13, Collicutt stated that they hadn’t yet printed ballots because they were waiting for the official Democratic nomination for president; Vice President Kamala Harris accepted the party’s nomination during the Democratic National Convention on Aug. 22.

“It’s really a moving target, and the law doesn’t set out anything definitively,” Collicutt replied. “But time is extremely tight…. Ballots go out on Sept. 6. I am prepped to send to the printer as soon as the presidential candidates are set.”

An unfair advantage?

One of the final questions lingering in the minds of the complainants that did not make it into the final grievance is the question of Clark and Rep. Clemmons’s relationship.

In an interview with the News & Record on Aug. 3, Kirkpatrick is quoted as stating how Clark “shadowed Ashton Clemmons during the last term.”

This has caused some of the other candidates to question whether or not Clark was hand-picked by Clemmons to take her seat.

When TCB initially reached out to candidates in mid July to conduct interviews for their campaigns, Clark was the only candidate who declined an interview, instead stating that she was “keeping [her] focus on personal outreach to the 65 executive committee and precinct chairs who will be voting on Ashton’s replacement on 8/3.”

That response from Clark was dated on July 22.

Emails forwarded to TCB show that Kirkpatrick sent out a list of precinct officials to the candidates so they could start campaigning on July 20. But in an interview, Kirkpatrick alluded to the possibility that Clark got a hold of a list prior to the other candidates.

“I have no idea where she got the list of precinct chairs and vice chairs,” Kirkpatrick said. “I sent it out to every person running. I didn’t even know she was running until she had made the announcement, and she already had the list at that point.”

Another timestamp indicating that Clark may have known about Clemmons’s plans to resign before other candidates is the fact that she had a campaign website, which was registered, according to a domain search, on June 25, about three weeks before Clemmons’s post on X.

Despite some of the connections between Clark and other Democrats, Kirkpatrick was clear in that there was no collusion on the part of the official local party.

“That absolutely did not happen from the party,” she said. “I know that individuals within the party were supporting some candidates, but the party itself? Absolutely not.”

Reached via email, Clark declined to comment on the ongoing controversy and questions about her relationship with Rep. Clemmons.

Magid told TCB that “it is not appropriate for [her] to comment at this time.”

Calls and emails to Rep. Clemmons went unreturned.

Looking toward the future

Now, as the complainants wait for the hearing on Aug. 25 to take place, they say they hope that some clarity of the process comes to light. And while it is unprecedented, if they’re accusations are correct, Gladden said that they want the elections to be redone.

“I don’t think there was any unintentional unfairness,” Wilson said. “I think we’re looking for a clear explanation of why the process was different. Whatever the outcome is, I will accept it.”

Alston said that he wants to hold the Democratic Party to a higher standard and this grievance is part of that process.

“I hope that we as Democrats always try to make sure to do things the right way,” he said. “If there’s any doubt about the election, we should recall this election and have it done over properly and it should be monitored by someone from the state and not the local Democratic party.”

One of the candidates, Tracy Furman, who is white, said she’s seeking to have her own questions about the process answered. In an interview on Aug. 19, she told TCB that she is planning on filing her own grievance to the Council of Review.

“We’re supposed to be the party of integrity and honesty and we totally believe in fair and open elections,” Furman said. “And yet, I don’t believe some of the actions in this were anywhere close to that.”

The move by the complainants to seek clarity in this process comes in the wake of the resignation of other state representatives. Rep. Jason Saine, a Republican representative for Lincoln County, and Sen. Jim Perry, a Republican for Lenoir County both resigned in July. And on Aug.15, Republican Rep. John Faircloth, another Guilford County representative, announced his plans to resign on Sept. 6. This will trigger a process similar to the one embarked upon by the Democrats just a month ago to replace Ashton Clemmons.

For candidate Allen, he said he wants to understand what happened, but then wants to ensure that the Democratic party can coalesce and unify behind one candidate.

“I do think that even though we have disagreements on things, the most important thing is to look forward to making sure to keep the seat Democratic,” he said. “And also fixing the issues that we went through so that we don’t have to address these issues again and we can improve things moving forward.”

Read a copy of the full grievance here and here.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply