Jane Marsh was 15 years younger when she met him.

As volunteer for the American Cancer Society, she arrived in 1999 at his house in High Point to transport him to his doctor appointments. They were strangers then, a fact that would quickly and unexpectedly change when Jane asked him a simple question: Can I take your picture?

Jane, whose résumé includes decades of experience as a commercial photographer, was drawn to this man. His rich character made itself known through bright blue eyes and burst forth from a smile that looked ready to reach beyond its face.

“I was enamored from the first time I saw him,” she said.

Surrounded by spare car parts, well-fed cats and trash bags, the man she would come to know as Smiley or Mr. Smiley emerged through a rickety screen door.

When they met, Smiley’s cancer was in remission. He was lanky and looked like he could hardly stand; he used a cane to walk, “yet he had this intelligence in his eyes,” she said. “I thought he was a gentle soul.”

Their relationship was unusual and unexpected, and anyone who saw them likely wondered what they were doing together, Jane said. It could be her posture, height or the dashing portrait from the 80s by a friend that hangs over her mantle, but Jane emits a soft glamor.

When she knew him, Smiley had a bent wire frame. He was sharp and with it, Jane said, but her description conjured a less gregarious image that the woman recalling him, someone who was personable to those who looked past his aged exterior.

She described Smiley as well put together, but Jane a little more refined. As she put it, they grew up near each other but likely on different sides of the tracks.

Some relationships are built on love, convenience or money, but not this one. Jane and Smiley bonded over a shared interest, but their relationship fused on a deeper level than that, slipping together and providing a connection the each seemed to need.

It isn’t that Jane didn’t have close relationships — listening to her talk about her family, particularly her twin brother, makes that clear — but Smiley offered something that was just… different. It sounds serendipitous, mildly bizarre and absolutely fitting all at once.

Jane, who said she has “dodged back and forth between Episcopal and Methodist,” discovered the volunteer program through a friend at church. Smiley was her first assignment, and Jane looked ready to explode with joy recalling the serendipitous first pairing.

“What a gift waiting for me,” she said.

Unsure how to broach the subject of taking his portrait, Jane waited several trips before asking. Smiley had seen better days, and she was nervous that he would misinterpret why she wanted to document him.

She finally asked, a decision that immediately altered their relationship and dramatically influenced her life.

“Oh honey if his face didn’t light up,” Jane recalled, sitting in her house folded off of Lawndale Avenue in Greensboro.

Overjoyed, Smiley posed on the steps in front of his house. Wearing a slightly baggy flannel shirt, jeans held up by black suspenders, sunglasses and a knit hat, Smiley grinned as he gripped the doorframe for support.

“How do you like my astronaut socks?” he asked her, motioning to the pair he was wearing.

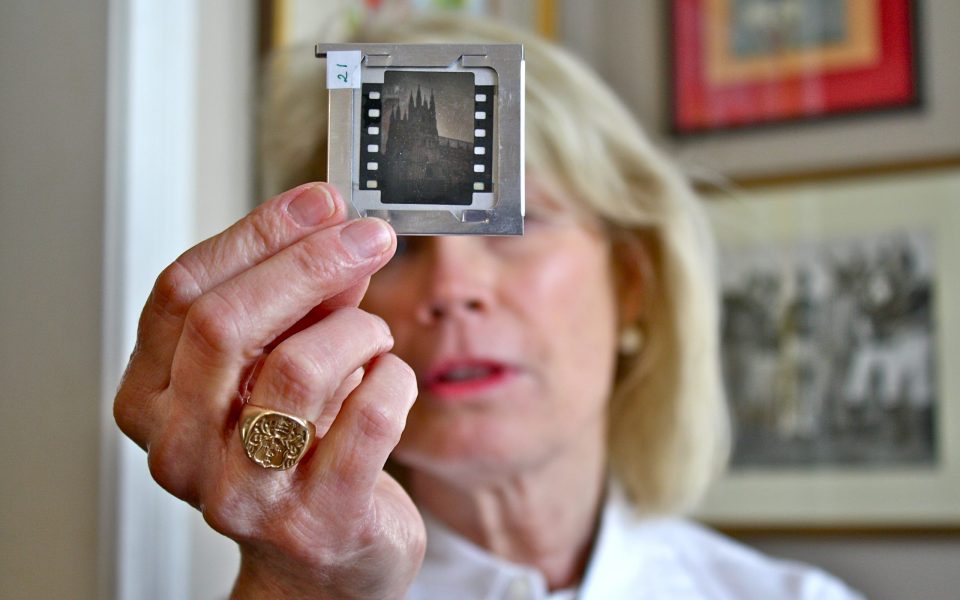

As they talked about taking his picture, Smiley revealed his own deep connection to photography. Out of the bottom of his closet, he retrieved 400 color slides that he took in the early 1950s during his time in the Air Force, stationed in Europe. He kept the slides — which he cut, assembled and numbered by hand — in a thin metal box, the same one he transported them in during his deployment.

And then, despite barely knowing her, Smiley gave Jane the whole box.

When she first took the slides home, laying them out on her dining room table and holding them up to the light, she wept.

“His eye, to me, is a beautiful thing to behold,” she said, adding that she is most drawn to the ones of people or cars. “It puts the romance and the time period, you know, the historical time that it was.”

But that isn’t why it made Jane cry. To see him so young, so handsome, and with so much ahead of him was difficult.

“I wept, you know, for the in between,” she said.

Smiley didn’t fight in World War II. He arrived after, his photos spanning across England, France, Belgium and Germany during 1951-54. He taught photography and even had a darkroom in England, and facilitated a photography club.

“Everybody had these fancy cameras and nobody knew how to use them,” he told Jane in his gruff voice.

The slides, all in color, show a cross-section of Smiley’s life: barracks and bases, crowds, architecture, vehicles, monuments, sloping landscapes and the photography club at a café. His mesmerizing shots evoke the precarious balance of the postwar period, seen on faces waiting for the Queen of England to pass in a procession, incomplete construction of a dome in Munich, his girlfriend resting on the wing of a biplane.

The evolving bond between Jane and Smiley extended beyond her charitable work. Their companionship remained platonic, she said, but they began talking frequently on the phone. On three occasions, they brought his slides to the Roy B. Culler Jr. Senior Center in High Point, Smiley narrating the shots through the clicking projector in the dark.

Jane, who calls herself “extremely sentimental,” knew immediately that something needed to be done with his photos, but didn’t exactly know what. She started recording their interactions on a borrowed tape recorder, eventually amassing four hours of conversations. She even looked up documentary-making programs, finding the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, but was intimidated and didn’t apply.

Jane’s voice is louder on the recordings; Smiley was hard-of-hearing when they met and often leaned in to hear her better. His narrations of the slides were punctuated by deep, rolling coughs.

He continued giving Jane pieces of his life — she’s lost her own high school yearbook but still treasures his. In it, his classmates suggest he might end up as the ambassador to France. Jane had long harbored a fascination with France but had never been. Smiley transported her across the Atlantic and back in time. Years later, she would retrace his steps in the snow to look up at the Eiffel Tower.

Jane, who would later drive other people with the American Cancer Society and volunteer with Hospice, knows the relationship was unconventional, and she’s not in the habit of breaking rules. In this particular case though, she said, it would’ve been wrong not to surpass the professional.

“I knew we were crossing a line but it was the right line to cross,” she said. “I would stampede right over it.”

At one point in the somewhat garbled tapes, Smiley summarizes their relationship.

“She ain’t my girlfriend, but I love the hell out of her,” he proclaimed.

The two admitted an affable love for each other, one that Jane recently described as a “complete, genuine, unconditional, authentic love.” There had been a void in her life, one she wasn’t exactly looking to fill, but their similarities drew them in.

“He knew me better than most people probably,” she said. “We just talked up a storm. We were both just shooting to the moon. Everything was just so much fun.”

Everyone who met the quiet, unassuming man was enchanted, she said, including a group of women from her former church who also helped him.

When Jane talks about Smiley, there is reverence in her tone. Sometimes she closes her eyes as she recounts a story, like the time she helped him get fitted for a suit so he could dress for church on Easter. Despite her initial protestations, he bought her a corsage.

It can sound like she she’s talking about herself: the gentleness, the glimmering blue eyes, the liberated laughter, the modesty, trademark smile and even their large cats.

Once he even told her that he knew the neighborhood in High Point where she grew up — he had a paper route there as a kid. Another time, sitting in the car without the tape recorder, he confided in her, sharing stories of secret missions across the demilitarized zone in Korea.

Jane didn’t believe him at first, thought his memory might be slipping, but later accepted what he shared as truth. Smiley was marked by his service and the time period, somewhat paranoid and possibly suffering from post-traumatic stress, Jane said.

She isn’t exactly clear what he did after the war, mentioning that he worked in the furniture industry, photography studios and with computers and that “he loved cars and he had something to do with automobiles. But what is clear is that he moved back to North Carolina and, later in life, met Jane.

When Smiley passed away in 2002, there was no obituary in the local paper or funeral. Jane and a few other people from the church held a makeshift service. In the hospital before he died, Smiley couldn’t speak but scrawled “Jane” in a notebook to ask for her.

“I did all the talking for both of us,” she said, adding that she would fill in his answers and he would nod to confirm. In the two hours she spent with him, Smiley didn’t take his alert eyes off her.

After Jane left, he let go.

Before he did, Smiley left a significant portion of his belongings and artistry with her.

“All that beauty and that art was in his head, and that intelligence,” she said. “He gave me all he had to give. He game me himself. He gave me his soul, he gave me his talent.”

She even has a plant that he gave her that’s still alive.

Thirteen years passed before Jane figured out where to begin with everything she collected from Smiley. Then, inspired by a local documentary she saw at a film festival at UNCG, she realized that making something with the 400 slides and four hours of audio was more manageable than it might seem. In 2010, she enrolled in the certificate in documentary arts program at Duke that she first found all those years ago, and started working.

“I knew I had the goods and they could teach me how to put it together,” Jane said. “He’s given me such rich material but I just hope and pray I do him justice.”

By creating an audio slideshow, she is incorporating her photos of Smiley, his vintage shots, the recordings of their time together, and narration.

Jane refers to her own voice as warbly and weak at times, but listening to her narration of her project is soothing, the kind of voice to listen to when trying to fall asleep.

When she listens to his voice on her recordings, sometimes Jane lip trembles, and she said that she laughs and cries listening to the tapes.

Jane didn’t think she would create a documentary project before meeting Smiley, and even when he turned over his somewhat rusted box of slides she thought she would do “a little something.” In retrospect, it makes sense.

“In the big picture it’s exactly what I’m meant to do,” Jane said. “Even if it’s just for this one time.”

The project, which she has titled Invitation to Trespass, has been far more technical that Jane anticipated and is incredibly time consuming. Her work station — a small table in a little area off of her living room — is decorated with headphones, white gloves, a cutting board, several screwdrivers, Q-tips and a cleaning liquid, all evidence of the manual labor required to transfer Smiley’s images into a digital format without ruining them.

Next to the equipment and her computer rest labeled white bags and rectangular red boxes filled with many, many slides.

“I could look at these for the rest of time,” Jane said, gesturing towards the containers of Smiley’s work. “It’s just like sitting and eating chocolate.”

There is still more work to do. Jane recently storyboarded the entire project with printed photos and last week obtained a photo of Smiley, herself and other women from the church group at the Easter outing. The audio, including music and vocal tracks, is ready, and many of Smiley’s images are already on her external hard drive.

On April 26, as the culmination of her certificate program at the Center for Documentary Studies, Jane will present her work. For now, she doesn’t have any plans to screen the 9-minute piece locally, though she’ll invite a few people who knew Smiley to the event.

But while Jane is eager to wrap up her audio slideshow that preserves Smiley’s photography and outlines their relationship, a part of her still wishes that she had been able to complete it before he passed away more than a decade ago.

“I think Heaven works some way that maybe he can,” she suggested.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

©

©

©

©

©

©

©

©

©

©

Thank you, Tim Swink, I just saw your comment and really appreciate it. Eric is a talented writer and I am grateful to him for sharing our story. I met Eric in a class while working on this project!

You were so nice to comment.

Jane

I love the story of Jane’s unusual friendship with Smiley and that will make it all the sweeter when I see the finished product…..the documentary she has been working on faithfully for quite a while now. I know it has been a labor of love. I know it is going to be excellent!

Harriet, thank you for this nice comment. I am so happy you will be attending the screening of our story!

Jane, I just read the story of your and Smiley’s friendship. (Francel had written about it on our Class of ’64 Facebook page.) It was such a lovely tribute to a man who would not have lived, as long as he did with out some one like you to encourage, love, give him something to live for. You exemplify an example of what it means to treat others in a Godly manner.

Pam (Kivett) Stanley

Pam, thank you for taking time to read this article by Eric and for your kind words. Smylie was a gift to me. Bobby Hoskins from our class and his wife Willodean were supportive and loving to Smylie as were others in the community. I was just one of the fortunate ones to meet and spend time with this man who had a big heart, personality, and talent to match. I hope you are well and that I get to see you in September! Thank you, Jane