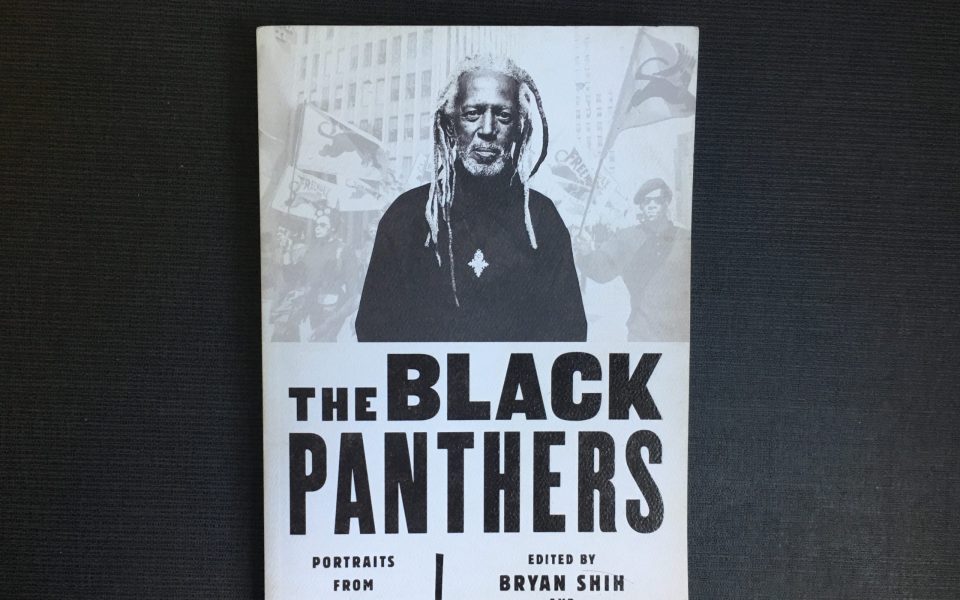

I’ve read a half dozen books about the Black Panther Party and probably watched an equal number of documentaries about the leather-clad revolutionaries. But there are a few things that set The Black Panthers: Portraits from an Unfinished Revolution apart.

Most importantly, the book edited by Bryan Shih and Yohuru Williams is a collection of oral history-style interviews with primarily rank-and-file members from across the country. Most accounts of the Black Panthers focus on the leadership, but this book’s strength rests with the everyday foot soldiers, ranging from New Orleans to Queens.

Some attempts have been made locally to commemorate and document the work of the Winston-Salem chapter of the Panthers — most noticeably a historical marker installed in 2012 — but they’ve largely been left out of the larger narrative. This book changes that.

Here, Nelson Malloy, Hazel Mack and Larry Little discuss why they joined the Panthers and talk about their time in the party, narrowing on the free ambulance service they established. Mack, who later founded the Carter G. Woodson charter school, details the branch’s lesser-known efforts, including a pest-control program. She also describes how the FBI failed to divide them and the local NAACP using fake letters.

“It got to be a real joke because people would bring us the letters,” she said. “We knew each other. These were people you grew up with.”

Malloy, who ran the free ambulance program, explains how the operation worked, revealing that the Panthers actually partnered with Bowman Gray Stadium. Malloy also describes how he survived an assassination attempt by fellow Panthers as the organization fell to ugly infighting.

Little is perhaps the most well known locally of the three, his name appearing repeatedly in these pages for his continued activism and scholarship. But you likely don’t know the gripping stories he offers in the book, including one about how the Panthers faced down the Klan.

“One time the KKK said that black children had lice and that they were going to stop all black kids who got off the bus and inspect them before they could go to the white school,” Little said. “We told them they were not going to do any such thing.”

Winston-Salem also receives a shout-out in one other interview, where Phyllis Jackson describes interviewing Panther women about how their families reacted when they joined the party.

“This one comrade, Haven Henderson, from the Winston-Salem chapter, said her mom came down in a fur coat and a Cadillac and said, ‘What are you doing down here? Come home!’” she recounted.

Accompanying the dose of local history, The Black Panthers is also a worthwhile book for its moving photography. Large portraits of each Panther take up full pages accompanying each interview. The photos are all contemporary, bringing this history to life, and illustrating the Panther alumni among us.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply