by Brian Clarey

The shuttle ran up the short hill on the campus of High Point University, depositing guests on the veranda of Phillips Hall, by the third fountain along the thoroughfare.

They came in dignified shades of black and gray, ate from catered hot trays and mingled on the hardwood floor before easing into the lecture hall for the premiere, the whole point of the evening. A promised discussion afterwards only sweetened the deal.

High Point: A Memoir of the African American Community is Phyllis Bridges’ first film, inspired, she said, by the realization that the history of her people, in her city, is largely unrecorded.

“High Point’s African-American history is not talked about,” she said in her remarks on opening night, “but I’ve learned so much. I have a better understanding of why High Point is the way it is. Stuff I never thought of — we know about the things that went on nationally, but not what’s here on the ground.”

And it’s important to note that Bridges is not a filmmaker. But she is an artist — Yalik’s Modern Art was her place on Washington Street before it shut down last year — and has been involved in her community for years in both volunteer and appointed capacities.

More important than her filmmaking credentials is the story she was trying to tell — is still trying to tell — to the people for whom it will have the most meaning.

When the city of High Point was incorporated in 1859, among its population of 525 people were 70 slaves and 14 free men of color. Earl Ijames of the NC Museum of History explained after the screening that Piedmont areas like High Point had mostly “woodchopping slaves,” as opposed to plantation hands in the cotton fields to the east of Raleigh. Influence from Quakers and Moravians, both of which abhorred the practice of slavery, allowed for a relatively robust population of free African Americans.

It was a Quaker who brokered the deal for the first piece of land in High Point to be owned by an African American, a 40-acre stretch along Eastchester Road purchased in the Quaker’s name.

Bridges breaks the film down into chapters of significance to the African-American experience, introduced with narration and colored with oral history.

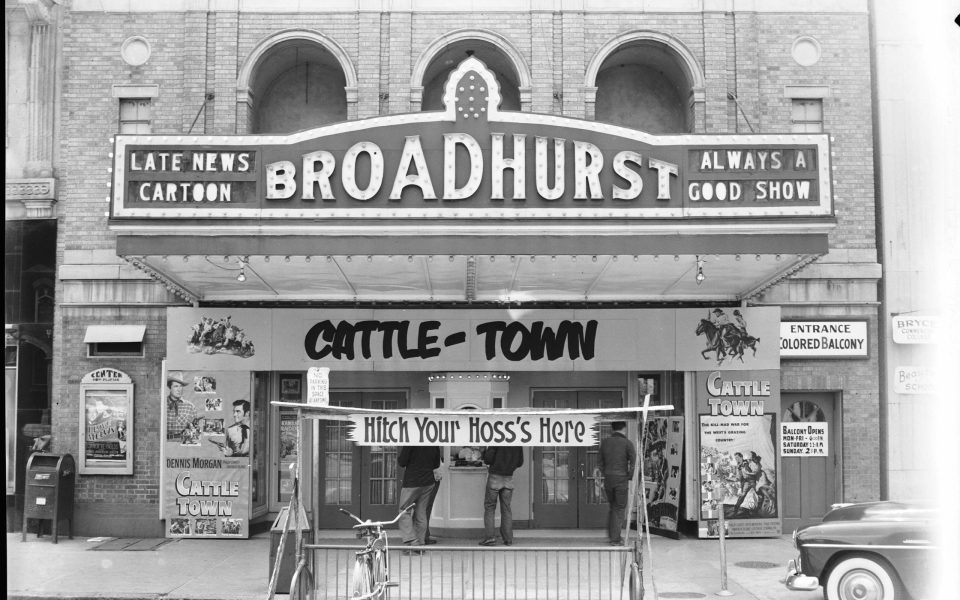

In the Jim Crow section we learn that a 1915 city ordinance prohibited restaurants from serving blacks and whites together by order of the health department.

Gilbert Carter, a retired furniture maker, said black folks rarely ventured into the white parts of town.

“You didn’t get too far across Green Street,” he said, reflecting Green Drive’s former name.

Albert Campbell, a former city magistrate, gave context: “You stayed within the bounds. You knew your place and you stayed in it.”

Jerry Mingo, a retired production supervisor who played in the William Penn High School marching band, recalled that they wore castoff uniforms from Central High, and that because of their scarcity only the musicians at the outer edge of the parade formation wore full dress. Scenes concerning the Kilby Hotel were stolen by former maître ‘d Randolph Reed, describing a walk across the Kilby Bridge and up Washington Street, “to show off my new suit.”

High Point’s first documented civil rights protest came well before the Greensboro Sit-Ins in 1960. Six years earlier, in December 1954, Dr. George Simkins and Dr. Perry Little insisted on playing golf at the city’s Blair Park course. A year later, Simkins would famously be arrested for trespassing at the Gillespie Park course in Greensboro, a case that went before the state Supreme Court in 1957.

Far from a comprehensive tableau of the black experience in the city, and suffering as it did from Bridges’ lack of filmmaking experience, the film nonetheless resonated deeply within the room.

A follow-up discussion with the filmmaker that included Ijames and community activists Mary Lou Blakeney and Albert Campbell served as a forum for the most stimulating material of the evening.

Ijames described the construction of the Great Western Plank Road and the railroad in the middle of the 19th Century, both of which ran through High Point, as integral to the African-American history of the city.

“North Carolina attracted a lot of black men of high ability, hard workers who could get a job done,” he said.

Reed, the maître ‘d, stood at his seat and described a forgotten social scene on the south side of town that included drinking corn liquor at the IDK Club, and gangsters named Bill Payne and Artel Woods. He also claimed to have thrown rotten tomatoes at the Guilford County Courthouse the night Strom Thurmond announced his run at the presidency for the States Rights Party in 1947.

A man in the crowd contextualized this forgotten history.

“Why do you think these things are not talked about?” he asked. “Why do you think this apathy plagues our community right now?”

The furniture and textile mills played a role, he said.

“When we were kids, every summer and vacation we went to the mill and worked alongside our parents,” he said. “If you were good at it, your parents might say, ‘Don’t bother going back to school. You can work here for 25 or 35 cents an hour, and you’re not gonna do much better than that.’”

Nods of agreement bobbed through the room as he discussed other issues in the community that have their roots in the past.

“Is this stuff we’re so rooted and grounded in, that we can’t help ourselves?”

“You see, Phyllis, this is what you started,” Blakeney said from the dais. “We need to be talking about this. This place should be packed.”

High Point: A Memoir of the African American Community next screens on Saturday at the High Point Public Library and on Jan. 31 at the NC Museum of History in Raleigh for its annual African American Cultural Celebration. Find out more at highpointmemoir.com.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply